Many Americans only experience government bureaucracy when dealing with the IRS or DMV, and in the popular imagination these interactions are known for being almost comically time-consuming and complicated. But for people who receive public benefits, bureaucracy is a more routine obstacle.

All too often, benefits programs are designed with an eye to the convenience of the administrators, not the clients. Lengthy forms full of jargon and fine print can be a big obstacle for someone who speaks English as a second language; commuting to distant agency offices is challenging for someone who lacks transportation and can’t take time off work. Accessing benefits sometimes involves a logistical high-wire act, and ad hoc, inconsistent processes effectively deter people who need these benefits the most.

Policymakers and researchers are beginning to recognize this problem. In some cases, however, attempts to ease access bring in people who are relatively better off—people with higher incomes, education levels, and language skills. Meanwhile, the people with the greatest hardships are less likely to take advantage of support systems primarily designed for them.

Now, a new study from the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford University offers insights into a time when lightening the paperwork and confusion surrounding a public benefit did get a bigger response from the neediest beneficiaries.

The researchers studied a reform that made it easier for low-income immigrants to apply for citizenship free of charge. When the convoluted fee waiver request process was replaced with a single form, they found, about 73,000 people per year became citizens who otherwise wouldn’t have applied.

It may sound like dull, procedural detail, but reforms like this go a long way toward making sure that programs for the disadvantaged actually work as intended. And in this case, all the red tape interfered with the principle that U.S. citizenship should be open to all who are eligible, not just those with means.

Equal Access to Citizenship

Keeping citizenship affordable is a rising priority for policymakers and immigrant advocates in the United States. The application fee, now $725, has risen sharply over the past few decades, creating a new barrier to citizenship.

At the same time, the federal fee waiver for low-income immigrants is curiously underused. Of the roughly 9 million immigrants eligible for citizenship, almost half are eligible for the fee waiver. Why don’t more people use it?

Before 2010, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) used a pretty opaque process for fee waiver requests. Immigrants demonstrated their inability to pay the application fee with either an affidavit or an unsworn declaration. USCIS officers used their best judgment in evaluating the claims, as there were only vague guidelines governing whether a claim should be approved.

Then, USCIS introduced a streamlined, transparent process: a simple form (the I-912) and clear rules for eligibility (receipt of any means-tested benefits, like SNAP or Medicaid, or household income below 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines).

“We were excited about this study because the standardization was a major policy change with the potential to affect millions of immigrants. It was also relevant for current debates about the future of the fee waiver program,” said Vasil Yasenov, a postdoctoral fellow at the Immigration Policy Lab and lead author of the study.

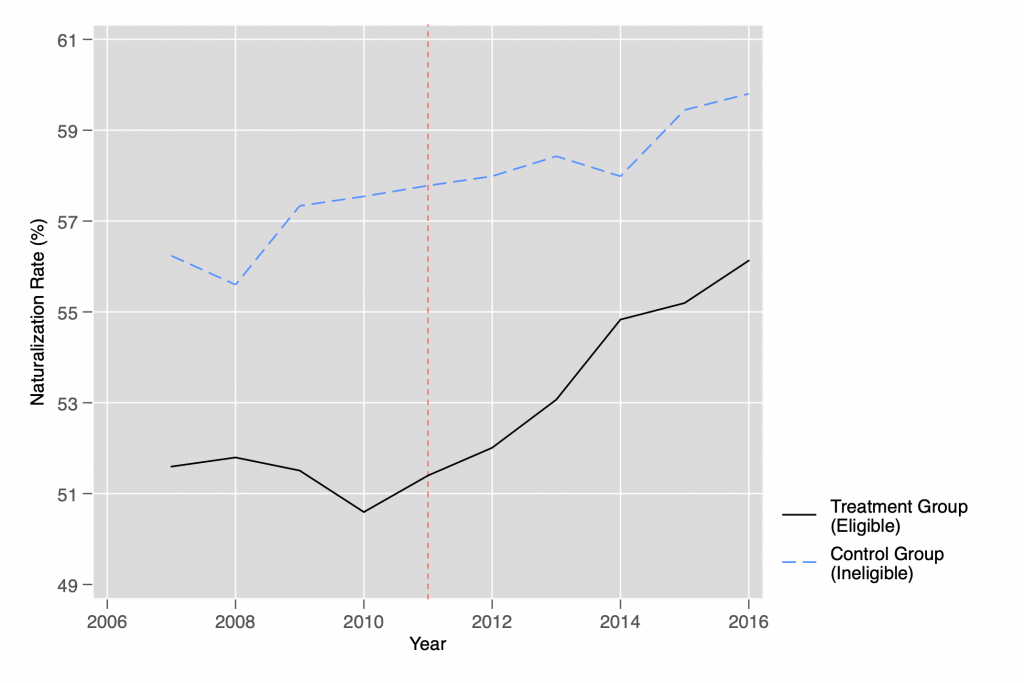

The researchers looked at 739,301 low-income immigrants who met the eligibility requirements for citizenship between 2007 and 2016 using data from the American Community Survey. They divided them into two groups to compare: those who would likely qualify for the fee waiver and those who wouldn’t. Other than income and employment, the two groups looked very similar. They were composed of roughly the same proportion of ages, ethnicities, origin countries, and time spent living in the United States.

After the fee waiver reform, the group eligible for the fee waiver naturalized at higher rates than the comparison group. The researchers found that there was no difference in trends between the two groups beforehand, but afterward a gap of 1.5 percentage points opened between them. That amounted to about 73,000 new citizens per year.

The Role of Non-Profits

As they delved further into the data, the researchers were intrigued to find an outsized response from those who could be considered least likely to naturalize—in other words, people whose circumstances make it particularly difficult to successfully apply. If you think of this group as most likely to be deterred by the cumbersome process surrounding the fee waiver before 2010, it makes sense that they would also be more likely to change their behavior once that obstacle was lifted. But this finding contrasts with research showing that it’s people with greater advantages in life who respond most to these kinds of “user-friendly” reforms.

What explains the anomaly? There was something else at work, something that helped translate the procedural changes into a positive force in people’s lives. That something, the researchers thought, was the hundreds of nonprofits and community-based organizations across the country devoted to serving low-income immigrants, known as immigration service providers. While they are in the public eye when engaging in political advocacy and community organizing, they are less well known for the everyday work they do: providing legal advice, referrals to health care or adult education programs, and help filling out naturalization forms.

As it turned out, their work was reflected in the data. The fee waiver reform has a greater effect among immigrants living in states with a higher density of these supportive organizations. And an additional survey of low-income immigrants found that those who received help from an immigration service provider were 21.5 percentage points more likely to use the fee waiver.

“With the I-912 form and the standardization of evidence needed for a fee waiver, organizations have been able to set up efficient processes to assist low-income immigrants who may have thought that their dreams of citizenship were out of reach because of the fees normally required to apply,” noted study co-author Michael Hotard.

Immigration service providers may soon play an even more important role in making citizenship possible for low-income immigrants. USCIS has proposed making fee waivers more difficult to get, narrowing eligibility criteria and requiring a tax transcript as proof of inability to pay. While immigration service providers will rally to help immigrants navigate the potential changes, cities and states can promote the fee waiver program and experiment with public-private partnerships to offer financial support for immigration fees. As with the 2010 fee waiver reform, a little creativity goes a long way.

LOCATION

United States

RESEARCH QUESTION

How do low-income immigrants respond to changes in the federal program that allows them to naturalize for free?

TEAM

Vasil Yasenov

Michael Hotard

Duncan Lawrence

Jens Hainmueller

David D. Laitin

RESEARCH DESIGN

Difference-in-Differences

KEY STAT

About 73,000 more immigrants per year became citizens after USCIS streamlined the process to request a fee waiver.