Being able to drive legally allows some unauthorized immigrants to work longer hours and increase their income. But for those who don’t already have a job, a driver’s license doesn’t boost their chances of becoming employed—lack of legal status remains a significant barrier to their job opportunities. IPL researcher Hans Lueders talks about his study of California’s policy opening access to driver’s licenses and what it can—and can’t—do for immigrants without legal status.

Q: This is your second study exploring the effects of policies that offer unauthorized immigrants access to a driver’s license. Among all the challenges faced by unauthorized immigrants in the United States, why did this issue—being unable to drive legally—capture your attention?

Hans Lueders: The simple answer is that being able to drive is so fundamental in this country for basically everything in life. I’m from Germany, where public transportation is far more widely available, which means that many people don’t really need a car to get to work, go grocery shopping, or take their kids to school. But if you don’t have a car in the United States and don’t happen to live in one of the few urban areas that have good public transportation, you don’t have access to anything.

That was really mind-blowing to me, and I could see that for people who cannot drive legally, this must have huge consequences for their lives.

Q: Have states always blocked access to driver’s licenses based on immigration status? When did they begin to shift toward opening access?

HL: Technically, any immigrant could get a driver’s license in most states until about 20 years ago. But following 9/11, Congress passed the Real ID Act, which led states to require applicants for driver’s licenses to provide proof of legal status in the United States. This made it more difficult for unauthorized immigrants to qualify for a driver’s license. Over the past decade, states have passed laws to allow unauthorized immigrants to get licenses, and today 16 states have these policies.

Q: In seeking to understand how driving legally affects people’s lives, you focus on California’s AB60 reform, which, starting in 2015, gave unauthorized immigrants access to driver’s licenses. Why is California a good proving ground for this policy? What advantages does this context offer you as a researcher?

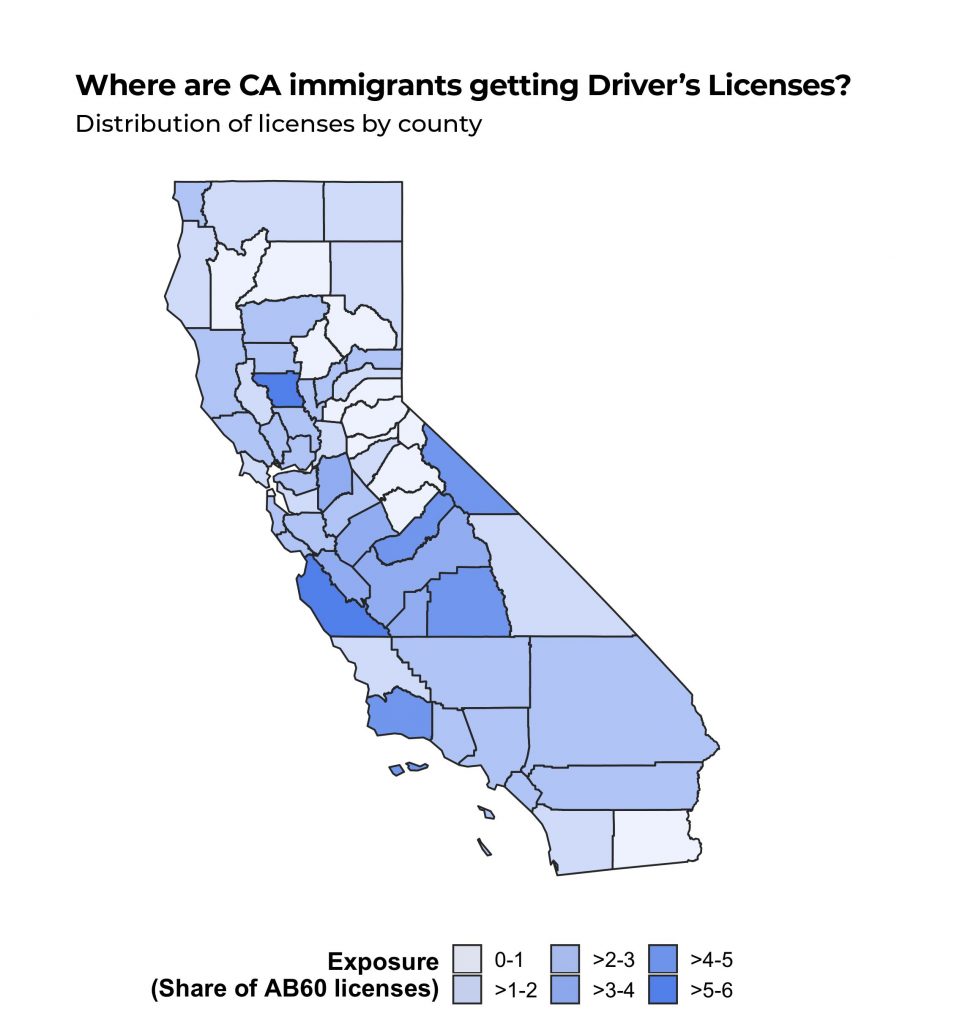

HL: First, California is the state with the largest number of unauthorized immigrants, so it’s really important to study this question there, just because it affects so many people. And second, in California unauthorized immigrants are not as concentrated in a few urban areas. For example, in Illinois most unauthorized immigrants live in and around Chicago, where there is relatively good public transportation. New York is similar: most unauthorized immigrants live in New York City and can rely on subways or buses. In California, they live in both urban and rural areas, so I expected that this policy would have a much greater effect there.

Q: How do researchers find out how many unauthorized immigrants live in each state, and where they live?

HL: This is very difficult, because unauthorized immigrants have strong incentives not to identify themselves as unauthorized to state authorities. We have very large, nationally representative surveys, like the American Community Survey, but these surveys don’t include questions about legal immigration status, and even if they did people probably wouldn’t answer truthfully. So what researchers do is select a subset of respondents who are likely to be unauthorized based on their social demographic characteristics—for example, people of a certain age, who entered the United States during a certain time period, come from certain countries, and have little formal education.

I used this method in my own study. I focused in particular on immigrants from Mexico who have less than high school education and arrived more than five years ago. However, when trying to develop the best method to identify unauthorized immigrants in the data, I found that among those unauthorized immigrants who have been in the country long term, many have been able to pursue education here, and they actually have relatively high levels of education. Dropping them from my analysis would provide only an incomplete picture of unauthorized immigrants in California. So I also used a second approach—looking at all non-naturalized Mexican immigrants in California irrespective of their level of education.

Q: What kinds of things can you learn from the American Community Survey?

HL: The American Community Survey, or ACS, is an annual survey of about 3.5 million households. People answer questions about their living situation, their income and occupation, and their use of private transportation, which is what I use in my study. The data goes to the Census Bureau, and researchers like me can see every person’s individual response—what we call “microdata.”

Using the approach I just described, the ACS allowed me to identify a group of respondents who are likely to be unauthorized. I could then use the ACS to see whether these respondents own a car, whether they use a car to get to work, how many hours and how consistently they work, and how much they earn.

With that data, I was able to compare the economic situation of likely unauthorized immigrants in California with that of similar people who have legal status, looking at these two groups over time and measuring how much change each group experienced after the policy was implemented.

Q: Going into the study, did you have any strong hunches or expectations of what the results would be? Did anything surprise you?

HL: Yes, I expected that driver’s licenses would have much larger effects on immigrants’ employment and earnings—mainly because there’s a large literature finding that owning a car improves these things among American citizens, and I thought there would be similar effects among unauthorized immigrants. But when I didn’t find these large effects, I thought more about the crucial difference between these groups, which is that unauthorized immigrants don’t have a work permit. So even if they can drive to work legally, they still face a significant barrier to employment.

Q: For those who do benefit from this policy change—those who already have jobs—how does being able to drive legally, rather than driving without a license, change the picture for them?

HL: I do find that immigrants who already have a job are able to work longer hours and increase their income. Some of them had already been driving before getting a license, because they had no choice but to drive. But legalizing their driving improves their situation because they now feel comfortable driving more frequently.

The AB60 law likely also helped people get access to cars, because car ownership rates increased. That means more people who don’t have to rely on friends or coworkers and neighbors to take them to work, which in turn means they can work any hours they want to, including early in the morning, late at night, or graveyard shifts. This can make a big difference for people working in agriculture, construction, and the hospitality industry.

It can also improve their mental health. I haven’t looked into this yet, because it’s really hard to measure, but once you have a license you don’t have to fear that any time you get pulled over by a police officer, it’s game over—that you might get deported. California’s AB60 law states that police are not allowed to use this kind of license to infer lack of legal status.

I’d also be very curious to see whether it makes people more likely to enroll in higher education, especially community colleges. Another interesting question would be how it affects internal migration—the idea being that once people have a car and can legally drive, they can more easily relocate to other places.

Q: In 2019, New York and New Jersey opened access to driver’s licenses after extensive debate that attracted nationwide attention. Is there anything you find encouraging or frustrating about this debate? Is there anything it might be overlooking or getting wrong?

HL: I think both sides operate on faulty assumptions about the driving behavior of unauthorized immigrants. Proponents usually say that offering licenses will improve their driving, because it will lead them to get tested and certified. Opponents assume it will introduce them to the streets as dangerous, inexperienced drivers. But I don’t see any evidence for either argument—I don’t find any change in traffic accidents and insurance premiums. This suggests to me that many of them had driven before.

And also, the debate often lacks a sense of how these policies can have positive effects for the communities in which unauthorized immigrants live. When they are able to increase their earnings, this benefits the local economy. When they don’t have reason to flee the scene of a traffic accident, hit-and-run collisions decrease. I think the public debate is not emphasizing this enough, but there is a lot of curiosity about the effects and a desire for evidence.

Hans Lueders holds a PhD in political science from Stanford University. He is a fellow at the Immigration Policy Lab and will be a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law in the coming academic year. He researches the political consequences of migration, focusing on unauthorized immigration in the United States and internal migration in Germany.

Learn more about his studies on this topic: Providing driver’s licenses to unauthorized immigrants in California improves traffic safety and Licensed to Drive, but Not to Work: The Labor Market Effects of Driver Licenses for Unauthorized Immigrants.