For many Americans, life without a car is unthinkable. Between long commutes, children’s activities and appointments, and all the errands that keep a household running, we can spend more time in our cars than at home. When the family car breaks down, those essential routines are thrown into disarray until it’s repaired.

For people without a driver’s license, including the vast majority of unauthorized immigrants, that unwelcome scenario is a daily reality. Unable to legally drive, they may find their choice of jobs restricted, educational opportunities out of reach, and medical care difficult to access.

When they do get behind the wheel, whether because they really need that out-of-the-way job or emergency doctor visit, they take a big risk: a minor traffic violation could lead to not only citations and fines for driving without a license, but also their vehicle being impounded and steep fees to get it back. At worst, a simple stop for a broken taillight could trigger deportation proceedings. These fears can lead unauthorized immigrants to try to avoid the police. In the case of an accident, they have an incentive to flee the scene, leaving the other driver in harm’s way and on the hook for the damages.

Multiply this dynamic by the entire population of unauthorized immigrants—California has the nation’s largest, at about 2.45 million—and it becomes a serious problem for traffic safety statewide. Recognizing this, some states have moved to make licenses available to unauthorized immigrants, reasoning that road safety will improve if more of these drivers are trained, tested, and insured. So far, 12 states and Washington, DC have made the change. It’s part of a broader trend in which states and municipalities are experimenting with more inclusive policies that incrementally bring unauthorized immigrants in from the periphery of society—usually in policy areas concerning public health and safety, where barring them from public services creates dysfunction that affects everyone.

The Impact of Inclusion

But moves to recognize the presence of unauthorized immigrants are controversial, especially when they involve official documents perceived as incorporating them into the mainstream of American life. When California’s AB60 law was under debate in 2011, opponents came out in force. Among other harms, the law would increase the number of accidents because, they claimed, many immigrants drive older, unreliable cars, can’t read signs in English, or are inexperienced drivers.

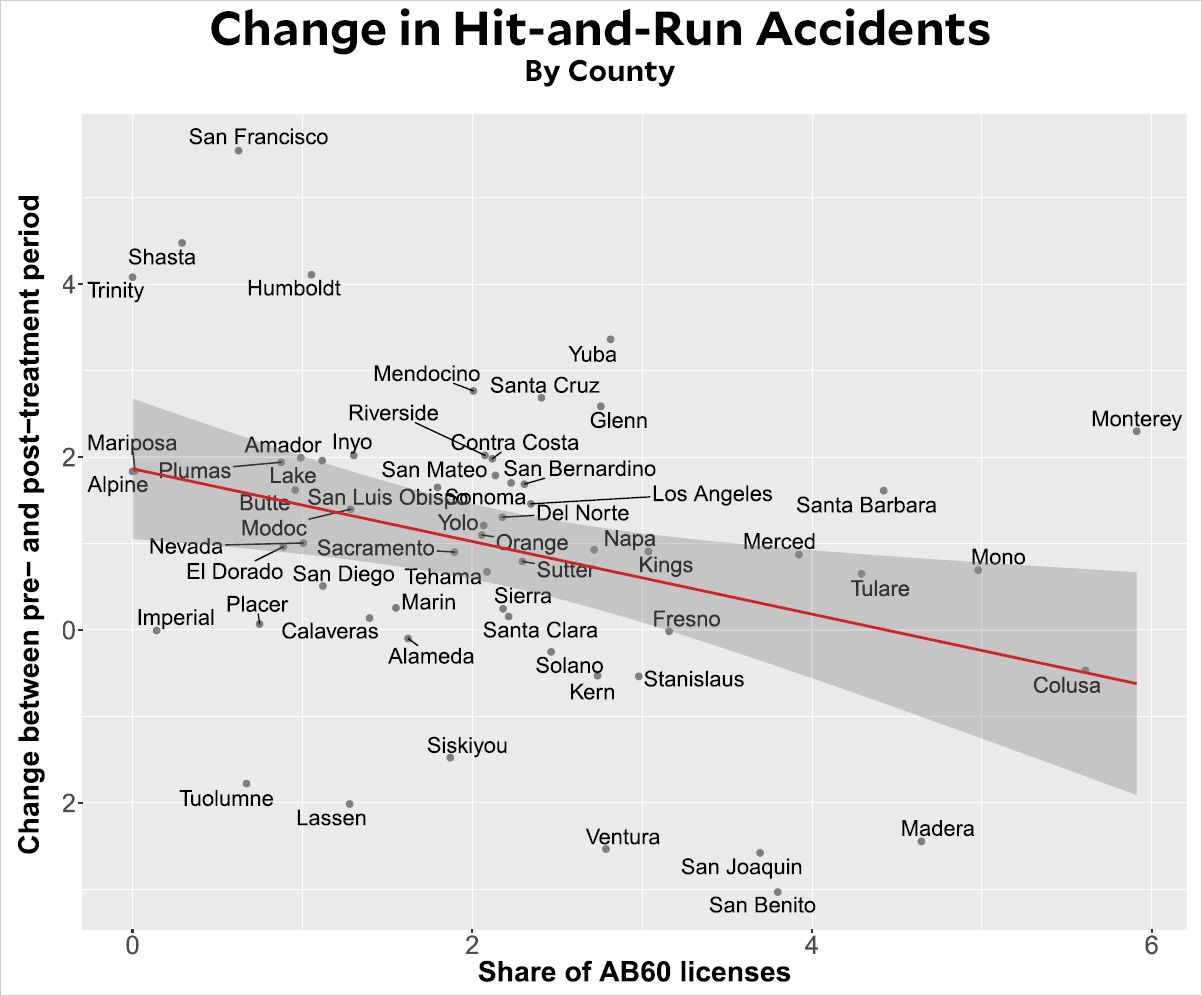

Were the critics right? IPL researchers conducted the first study to look for answers. With other states, including New York, weighing whether to follow suit, it’s important to know whether their warnings were borne out. In the time since California’s law went into effect, in 2015, more than one million AB60 licenses have been issued, providing data on a scale large enough to measure its consequences. What’s more, since unauthorized immigrants are concentrated in certain counties, we can compare changes in traffic safety in areas with many AB60 licenses and those with few.

The results were striking. Looking at the program’s first year, researchers found no significant change in the number of accidents per capita or in the rate of fatal accidents. Its effects were strongly felt, however, in the rate of hit-and-run accidents. In areas with higher numbers of unauthorized immigrants, hit-and-runs decreased by 7-10 percent over the year before, relative to the change seen in areas with fewer unauthorized immigrants. That means roughly 4,000 fewer hit-and-runs, amounting to nearly $3.5 million in savings for drivers who otherwise would have had to cover the costs incurred by the absentee at-fault driver.

Notably, looking at the uptake of licenses alongside new auto registrations suggests that many of the newly licensed had been driving before the policy shift. As the researchers explain, this points to the reason why hit-and-run accidents decreased:

AB60 explicitly prohibits law enforcement officers from reporting license holders to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Consequently, unauthorized immigrants with a valid form of in-state driving authorization have weaker incentives to flee the scene after an accident, because they are less likely to fear deportation.

Alternatively, unauthorized immigrants involved in an accident before the reform also may have been concerned about having their car impounded as a result of driving without a license. Fees to recover a vehicle after impoundment can easily exceed $1,000. Like most Californians, many unauthorized immigrants depend on their car to go to work, often driving long distances to get there. Losing the car to impoundment can jeopardize their income and employment, which presents another incentive to flee the scene after an accident.

Policymakers, understandably, may take stock of the political landscape and shy away from the controversy that comes with inclusionary programs for unauthorized immigrants. With evidence that these programs have benefits for all of their constituents, however, they can build greater support for positive reforms.

Given the centrality of driving to many people’s lives, California’s AB60 law likely had effects beyond the scope of this initial IPL study. IPL researchers look forward to studying its impact on other aspects of traffic safety, as well as local economies and labor markets.

Watch: The Difference a License Makes

LOCATION

California

RESEARCH QUESTION

When a state makes driver’s licenses available to unauthorized immigrants, what is the effect on traffic safety?

RESEARCH DESIGN

Difference-in-differences

KEY STAT

California issued more than 600,000 licenses to unauthorized immigrants in 2015

TEAM

Jens Hainmueller

Duncan Lawrence

Hans Lueders