In new research by IPL faculty affiliate Ran Abramitzky, names trace the patterns of immigrant families’ integration over generations.

What’s in a name? Quite a lot, according to new research by Stanford economist and IPL faculty affiliate Ran Abramitzky: during the era of mass migration in the United States, the names immigrant parents chose for their children were a meaningful way for the family to identify with American culture.

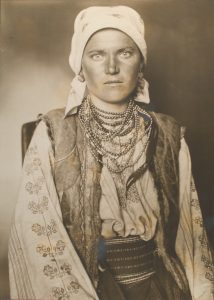

Other expressions of cultural integration are difficult to measure; no systematic data is collected about whether immigrants wore traditional clothes or blue jeans, ate borscht or BLTs, listened to folk music or developed an ear for American jazz. But changes in naming trends among various immigrant groups can be tracked through public records, and they tell a story about how newcomers wrestled with the desire to stay connected to their roots while giving their children a strong future in their new home.

In a study drawing on 4 million U.S. census records from the early to mid-20th century, Abramitzky and his co-authors, Leah Boustan (Princeton) and Katherine Eriksson (UC Davis), found that immigrant parents were more likely to choose American-sounding names for their children the longer they remained in the country. What’s more, that choice not only signaled parents’ motivation to take part in American culture; it also was associated with economic and social benefits for the child:

We examined the census records of over 600,000 children of immigrants, observed both in 1920, when they lived with their childhood families, and in 1940 as adults. Indeed, children with less-foreign-sounding names completed more years of schooling, earned more, and were less likely to be unemployed than their counterparts whose names sounded more foreign. In addition, they were less likely to marry someone born abroad or with a foreign-sounding name.

The findings invite us to consider the weight a name would have had during this time period. Imagine two immigrants, Abramitzky suggests, Vladislav and John. When introduced to new people, Vladislav is almost always asked, “Where are you from?” Even before his first day in a new classroom, the teacher can tell he is from an immigrant family, and any time he applies for a job the employer knows he’s of a different ethnic background. His name is a badge of foreignness, one John doesn’t carry. For many immigrant parents, perhaps fearful of discrimination, a name like “John” represented the hope that their child would have every opportunity for success in America.

Then as now, established Americans worried that immigrants were arriving in such large numbers that they’d never fully integrate into society, instead settling into parallel lives in ethnic enclaves. Those fears weren’t borne out, the study found:

Other measures reinforce the picture of early twentieth century immigrants gradually taking on American cultural markers. By 1930, more than two-thirds of immigrants had applied for citizenship and almost all reported they could speak some English. A third of first-generation immigrants who arrived unmarried and more than half of second-generation immigrants wed spouses from outside their cultural group.

The researchers observe similar patterns in naming trends among recent waves of immigrants in California. Even though their origins and entry routes look very different from those of the mostly European arrivals of the early 20th century, these new arrivals begin choosing American-sounding names over foreign ones at about the same pace as their predecessors, with Mexican and Vietnamese families making the shift more swiftly than others.

Cultural integration, the research reveals, is often an organic process, and policies intended to force it can be counterproductive, as fellow IPL affiliate Vicky Fouka has found. Looking at the example of classroom restrictions on foreign languages, Fouka discovered that forced assimilation can spark a backlash that leads immigrants to withdraw from civic life and identify even more strongly as an ethnic minority.

The findings carry a lesson for today’s highly fraught immigration debate: far from consigning themselves to permanent outsider status, as many fear, most immigrants come to share in the common culture and form identities as Americans.