In the polarized world of American politics, health care and immigration are potent wedge issues that arouse idealism and anxiety in equal measure. That’s all the more true when they combine: witness the political earthquake when every Democratic presidential candidate agreed that government-run health plans should include undocumented immigrants, a watershed moment that arrived soon after California expanded Medicaid coverage to undocumented young adults.

Critics sounded the alarm about a “magnet effect” and spiraling costs. Speaking at a legislative hearing, California state senator Jeff Stone embodied the opposition: “We are going to be a magnet that is going to further attract people to a state of California that’s willing to write a blank check to anyone that wants to come here.”

Yet not long ago, a significant expansion of health care access to immigrants happened with much less fanfare and controversy, even though it marked a turn toward more inclusive policy and affected millions of lives. And that trend can speak to current debates about immigrants and health benefits, thanks to new research from the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford University. According to IPL’s study, conducted in collaboration with Stanford professor of pediatrics Fernando Mendoza, there is little evidence that a “welfare magnet” draws immigrants across states seeking benefits.

A Patchwork of Policies

The landmark Welfare Reform Act of 1996 has been exhaustively debated, but it is often overlooked that the law affected immigrants, imposing a five-year waiting period before newly arrived immigrants could apply for Medicaid. Relatively few states stepped in to patch the new gap in insurance coverage for their low-income immigrant residents.

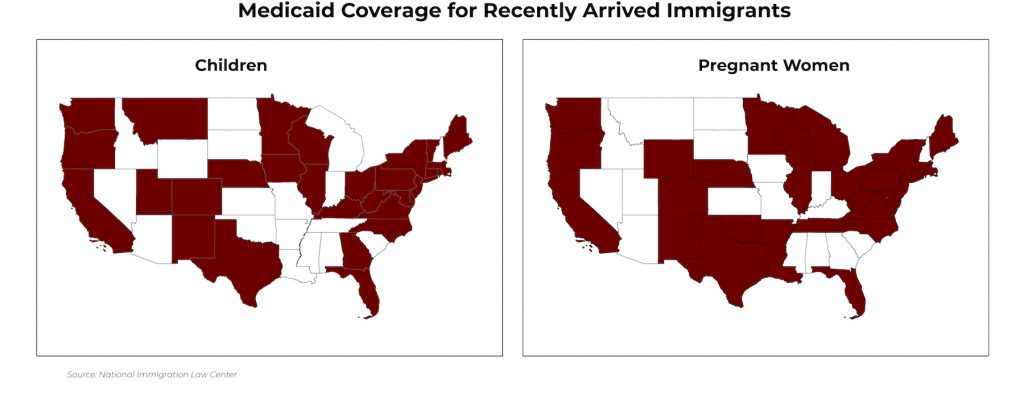

A thaw began with the passage in 2002 of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and its reauthorization in 2009 (CHIPRA). States could now use federal funding to help cover their uninsured or underinsured populations, including immigrant children and pregnant immigrant women. A wave of states welcomed these immigrants into their programs: in 2000 only 18 states offered coverage to immigrant children, and that number increased to 31 states by 2016.

Today, both political rhetoric and federal policy are returning to the “welfare magnet” notion that immigrants pose a fiscal challenge to social safety net programs like CHIP. But is there any evidence of this? IPL’s study of the response to CHIP suggests that immigrants don’t strategically move to other states to pursue public health benefits.

Today, both political rhetoric and federal policy are returning to the “welfare magnet” notion that immigrants pose a fiscal challenge to social safety net programs like CHIP. But is there any evidence of this? IPL’s study of the response to CHIP suggests that immigrants don’t strategically move to other states to pursue public health benefits.

“Our findings suggest that when states expand health benefits to immigrants, this has no measurable effect on whether immigrants choose to move to that state,” says IPL co-director Jens Hainmueller.

In a way, this is surprising, because previous research has found that immigrants are more likely to relocate in search of more favorable economic conditions. Immigrants also are more likely to lack health insurance, and expansions of health coverage tend to be popular.

“Given immigrants’ high mobility and the strong demand for health services, we expected that the expansion of public health care benefits in some states would be associated with immigrants relocating to those states, since the insurance coverage offers protection from financial burden and helps ensure their children’s access to care,” says IPL postdoctoral fellow Vasil Yasenov.

For immigrants facing barriers to health care, it’s no small thing to suddenly be eligible for coverage in a nearby state. Without insurance, many immigrants rely on the limited services available at free clinics or the scant coverage of a program offered by their city or county. Five years is a long time for a growing child not to see a care provider or for a woman to either forgo prenatal care or stall on having children.

Discerning Migration Patterns

But is this such a powerful draw that immigrants already settled here would uproot themselves and start over in a new state? The IPL researchers wanted to find out, and because the states responded to CHIP in different years, in a staggered fashion, they had an ideal setting for an experiment, with ready-made “treatment” and “control” groups.

They looked at 208,060 immigrants between 2000 and 2016, during the wave of states expanding coverage. In the “treatment” group were 87,418 women of reproductive age and 36,438 adults with at least one foreign-born child. Used for comparison were three groups that wouldn’t have any added incentive to move, not being eligible for the coverage: single immigrant men, older immigrant women, and immigrants without children born outside the United States.

Among all immigrants, about 3% moved to another state in any given year during the study period. Focusing on migration trends in states that expanded health coverage, the researchers found that immigrants were no more likely to move into a benefits-providing state if they were eligible for those benefits. The “treatment” and “control” groups had similar migration patterns before and after the expansions.

To home in on the groups with the greatest incentive to move, they looked at residents of neighboring states, and added U.S. citizens as another control group. Here too, eligible immigrants were no more likely than anyone else to move to a benefits-providing state. “Part of the explanation is that economic opportunity and social networks are a more powerful draw in these decisions than generosity of benefits,” says Yasenov.

Today, one in four U.S. children was born abroad or was born in the country to immigrant parents, and that number is expected to grow to one in three by 2050. The national conversation around the Affordable Care Act, and the major reforms it ushered in, helped forge a strong consensus that preventive care is not only vital for public health but also holds down costs—and that insurance is key to ensuring access to preventive care. In light of this, it’s inconsistent to categorically exclude newly arrived immigrants and their children, many of whom become long-term residents and citizens. Currently, up to 93,000 families could benefit from expanded coverage, the IPL researchers say.

“Given the widely acknowledged importance of pediatric and prenatal care for healthy child development, it is surprising how many states still do not offer coverage for these services to recently arrived green card holders,” says Duncan Lawrence, IPL’s executive director. “We hope policymakers who are considering expanding pediatric and prenatal health coverage to immigrants now have the evidence to allay concerns regarding a “magnet effect” across states.”

LOCATION

United States

RESEARCH QUESTION

Does expanding publicly funded health coverage to immigrants attract an influx of immigrants from other states?

TEAM

Vasil Yasenov

Duncan Lawrence

Fernando Mendoza

Stanford School of Medicine

Jens Hainmueller

RESEARCH DESIGN

Natural Experiment

KEY STAT

About 25 percent of children in the U.S. were born abroad or have immigrant parents.

FUNDER

Maternal & Child Health Research Institute, Stanford School of Medicine