For most American women expecting a child, many of the emotional milestones of pregnancy are experienced through medical care, from getting a glimpse of the baby’s face on an ultrasound to tracking his or her growth over months of appointments. For unauthorized immigrant women who are otherwise locked out of the health care system, prenatal care brings not just peace of mind but also an opportunity to address broader health issues. Since many of them can’t afford to purchase health insurance and are ineligible for Medicaid or Affordable Care Act subsidies, a prenatal care appointment may be the first time in a long while that they have met with a care provider and been evaluated for a number of chronic conditions.

As research has established the importance of prenatal care for newborns’ health, more states have moved to expand access to prenatal care for unauthorized immigrant women. Currently, 33 states offer them some form of coverage, either through state funds or the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which offers an “unborn child provision” for services benefitting a future U.S. citizen.

How do these inclusive programs affect immigrant women who generally lack access to routine health care? Clear answers can be hard to come by, because states that offer them differ in many ways from states that don’t, and because the limited data available don’t allow researchers to separate out the women who are directly affected.

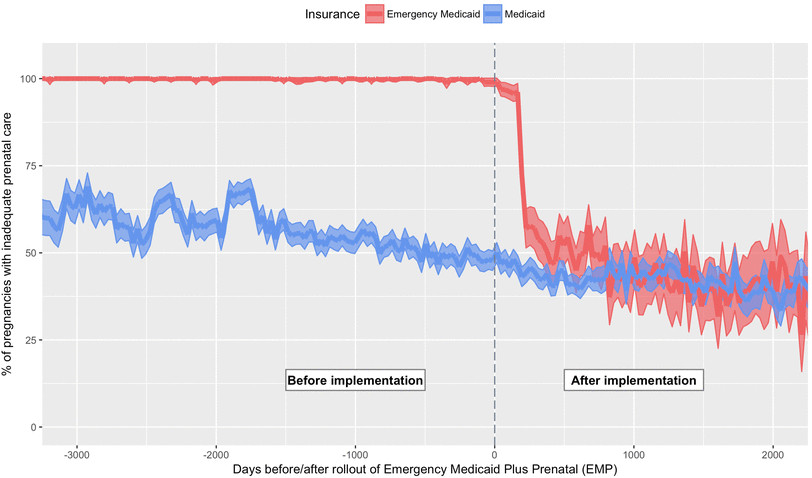

But beginning in 2008, Oregon gave IPL researchers a chance to overcome these challenges: when it introduced Emergency Medicaid Plus, which offered prenatal care coverage to unauthorized and recently arrived immigrant women, it launched the program in just two counties and then gradually added others over the following four years. “The structured expansion created a natural experiment by which to compare immigrant women who had access to prenatal care to those women who remained without access. Eligibility was determined by county of residence and therefore not subject to self-selection,”the researchers write.

Women embraced the program, the IPL study found, participating in high numbers. Before the program, almost all women who only had Emergency Medicaid coverage for labor and delivery received inadequate prenatal care; that number dropped by about a third afterward. And in turn, these women were more likely to be identified for pregnancy complications like gestational diabetes, poor fetal growth, and preeclampsia and related hypertensive conditions. Notably, the program also led to increased diagnoses of pre-existing diabetes, giving these women a chance to improve their own health long after the baby is born.

Whether these public health benefits are encouraged or left unrealized depends in large part on policymakers. The eligibility conditions they set for Medicaid, which pays for nearly half of all births in the United States, can make a big difference—especially for low-income, foreign-born women whose high-risk pregnancy conditions tend to go undiagnosed and untreated. Reflecting on the results, the researchers write:

Policymakers should consider the potential for long-term consequences for individual and community health when implementing policies that affect care during pregnancy. . . . Reduction of diabetes and obesity is a public health priority, and detection of high-risk conditions during pregnancy may mitigate the burden of chronic disease. . . . [O]ptimizing care during the antenatal period can have long-lasting health benefits for women and their children.

As some policymakers weigh whether to fund or renew programs like Oregon’s, and others consider imposing citizenship-based restrictions on access to care, it’s all the more important that they have this kind of evidence about the multigenerational effects of their decisions.

LOCATION

United States

RESEARCH QUESTION

When states grant access to prenatal care to unauthorized immigrant women, how do the programs affect their health and health care use?

TEAM

Jonas J. Swartz

University of North Carolina

Jens Hainmueller

Duncan Lawrence

Maria I. Rodriguez

Oregon Health & Science University

RESEARCH DESIGN

Difference in Differences

KEY FINDING

An Oregon program reduced inadequate prenatal care by 32% overall and by 39% among high-risk pregnancies.