In the years since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) made it a national priority to decrease the number of uninsured Americans, nearly 18 million people have gained health insurance. While applauding that success, however, it’s easy to overlook the large group of people mostly left out of the health care reform effort: unauthorized immigrants.

Many of them can’t afford to buy coverage on their own, and they’re ineligible for public assistance under Medicaid or ACA subsidies for low-income people. In California, which is home to about a quarter of the nation’s unauthorized immigrant population, an estimated 51% of them are uninsured. (Nationally, that figure is 41%, compared to 9% of U.S. citizens.)

These immigrants often forgo preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases. When they do receive care they rely on a patchwork of charitable organizations, safety-net clinics, and hospital emergency rooms, where caregivers may find them more difficult to treat than had they been able to access routine care earlier. Where there are large numbers of uninsured people, these aren’t just humanitarian concerns; they also increase costs and inefficiencies in local health systems.

Some states and communities are responding to the problem by creating more inclusive health programs. In Oregon, the effort began with a particularly urgent need: prenatal care. When a woman arrives at the hospital, hours away from giving birth, without ever having seen a physician or midwife during the pregnancy, her caregivers may not know her medical history or whether she has risk factors that make labor dangerous for her or her baby. Many unauthorized immigrant women found themselves in this situation because they lacked coverage for prenatal care, and they were at disproportionate risk for poor outcomes like infection, obstructed labor, and newborns with low birth weight.

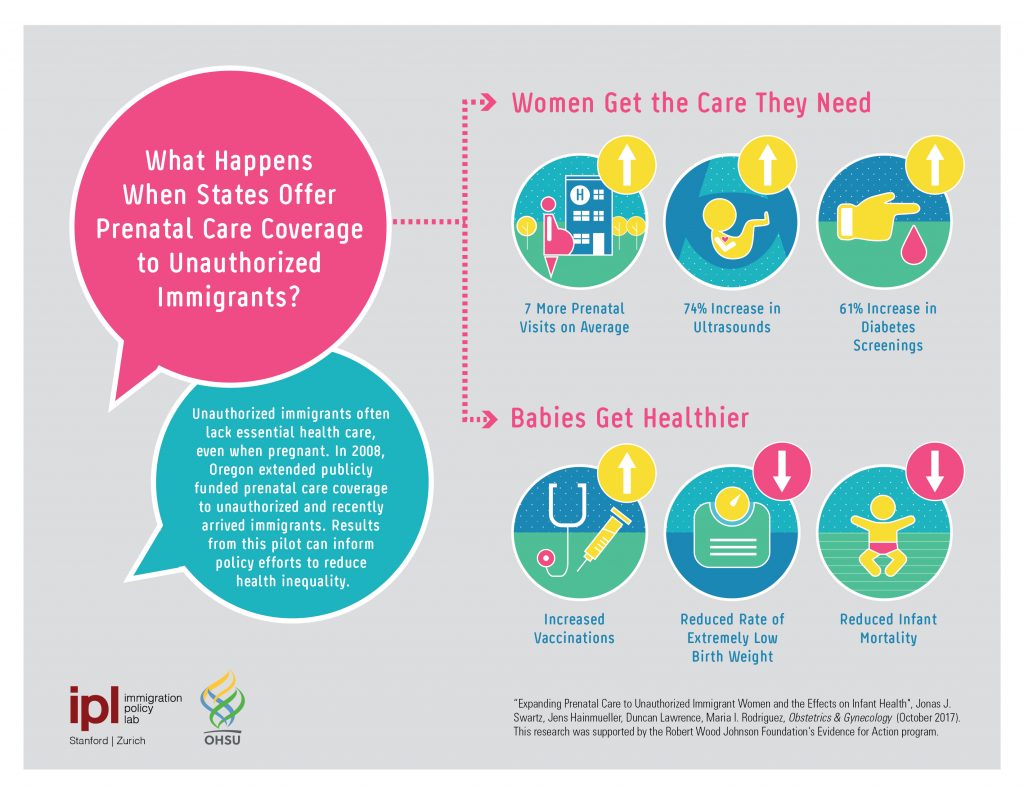

To remedy this, in 2008 Oregon began piloting an extension of publicly funded prenatal care to undocumented and recently arrived immigrants in two counties, Deschutes and Multnomah. The program, known as CAWEM Plus, expanded to four additional counties in 2009, seven more in 2011, and finally to all 36 counties in 2013.

The shift in policy over time at the county level allowed IPL researchers a unique opportunity to measure the impact of inclusive policies like Oregon’s. Working with colleagues from Oregon Health and Science University, they compared undocumented and recently arrived immigrant mothers and their children within each county, before and after the policy was implemented, with those in counties where the policy was not enacted until 2013. The results reveal profound benefits for immigrant women, their U.S.-born children, and for public health.

First, offering the coverage effectively brought women into the health care system. Compared with those without coverage, these women received an average of 7 more doctor visits; their rate of screening for gestational diabetes increased by 61 percent, and the number who received at least one fetal ultrasound increased by 74 percent. In turn, their babies were born healthier: rates of extremely low birth weight decreased, as did infant mortality. The program also set the children on a path for better health later in life: Women with access to prenatal care were more likely to bring their newborns in for well child visits, screenings, and vaccinations.

First, offering the coverage effectively brought women into the health care system. Compared with those without coverage, these women received an average of 7 more doctor visits; their rate of screening for gestational diabetes increased by 61 percent, and the number who received at least one fetal ultrasound increased by 74 percent. In turn, their babies were born healthier: rates of extremely low birth weight decreased, as did infant mortality. The program also set the children on a path for better health later in life: Women with access to prenatal care were more likely to bring their newborns in for well child visits, screenings, and vaccinations.

These results should encourage technocrats as much as they do social justice advocates and clinicians concerned about health disparities. Policies like Oregon’s not only make a difference in the lives of immigrants and their children, who are U.S. citizens; they also make the local health system run more efficiently and the population healthier.

While there remains considerable political resistance to opening access to health coverage for unauthorized immigrants, support might increase with evidence that there are broad benefits, such as lower levels of uncompensated care, as well as lower Medicaid costs associated with chronic conditions as people receive preventive care or treatment before those conditions become serious. As research puts the numbers to the human costs of leaving large populations outside the health care system, it can fuel the trend of state and local governments integrating unauthorized immigrants and their families into their public programs.

LOCATION

Oregon

RESEARCH QUESTION

What are the causal effects of access to prenatal care for immigrant women?

RESEARCH DESIGN

Difference-in-differences

KEY STATS

Unauthorized immigrants are 4% of the population but 15% of the uninsured

Obstetric admissions account for over 80% of care funded by Emergency Medicaid in Oregon

TEAM

Jens Hainmueller

Maria Isabel Rodriguez, M.D., M.P.H.

Oregon Health and Science University

Jonas Swartz, M.D., M.P.H.

Oregon Health and Science University

Duncan Lawrence

FUNDER

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action Program