Across Europe, countries once dominated by centrist politics are experiencing a marked surge in support for far right populist parties. In France, dissatisfaction with President Emmanuel Macron’s government has bolstered support for the far right National Rally party, which surpassed 30% in the latest polls. As parties in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Hungary, and Portugal gain traction, the far right is projected to win more seats than ever before in the upcoming EU Parliament elections in June. Among several key issues these parties are running on—including Russia’s war with Ukraine and the rising cost of living—immigration has become a prominent concern.

This is a strategic choice: the discourse on immigration is particularly prone to myths, making it easily exploited by far right populist movements. Fringe groups stoke fears and blame a myriad of societal issues on migrants—and this narrative is then echoed in the media. Within the social sciences, hundreds of studies examine the relationships between public attitudes about immigration and voting behavior. But has all this focus on immigration caused us to overlook other demographic factors fueling the rise of anti-immigrant far-right parties?

An IPL study points to a potentially more influential but less-studied phenomenon: emigration, or the movement of people out of a region or country. Emigration is an increasingly common phenomenon as younger people leave the smaller towns they grew up in to seek out educational and employment opportunities in larger urban centers. Looking at demographic trends and voting patterns over a 16-year period, IPL researchers found that the departure of people from their communities of origin contributed to a rise in support for radical right populism in such places. They identified two key mechanisms driving this relationship: 1) a change in the composition of voters in remaining communities, and 2) a shift in the political leanings of those voters in response to the negative effects of local population decline.

Growing Radical Right Populism

The study first identifies two trends: out-migration from municipalities across Europe, and an increase in support for populist radical right parties. As the map in figure 1 shows, populations across 112,028 municipalities in 32 European countries were in flux between 2001 and 2011, with some areas gaining at a rate of more than 2% annually, and others declining. In regions experiencing the greatest population declines, emigration is a key driver.

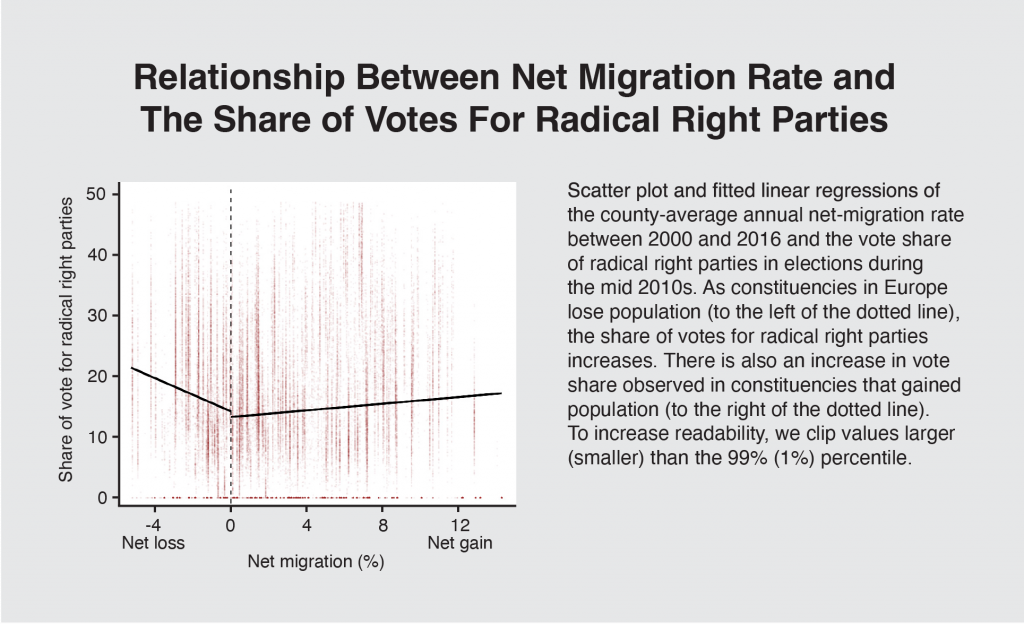

The researchers then looked at how radical right parties fared in national elections during this period. Across 28 European nations, they found a correlation between out-migration at the county level and increases in vote shares for populist radical right parties (see figure 2).

Sweden’s Right Turn

To better understand and eliminate alternative explanations for this trend, the researchers conducted an analysis of a single country where political, economic, and demographic trends mirror those of other high-income, democratic nations: Sweden. A relatively popular destination for immigrants, the proportion of immigrants living in Sweden increased from 11% of the population in 2000 to nearly 20% in 2020. At the same time, 51% of Swedish municipalities experienced population decline, a figure that matches trends across Europe as a whole.

Swedish politics have long been dominated by the center-left Social Democratic party. Featuring organized blue-collar workers and public sector employees, it is Sweden’s oldest and largest political party. After enjoying strong public support since the 1920s, the Social Democrats have experienced a slow decline in popularity over the past few decades. In 2022 they won just 30% of the vote, down from the over 40% share they held from the 1940s through the late 1980s. Meanwhile, the Sweden Democrats (SD), a once-fringe radical right party founded on a nationalist and anti-immigrant platform in the 1980s, has experienced dramatic gains in popularity over the past few years, and today are a coalition partner in the Swedish government.

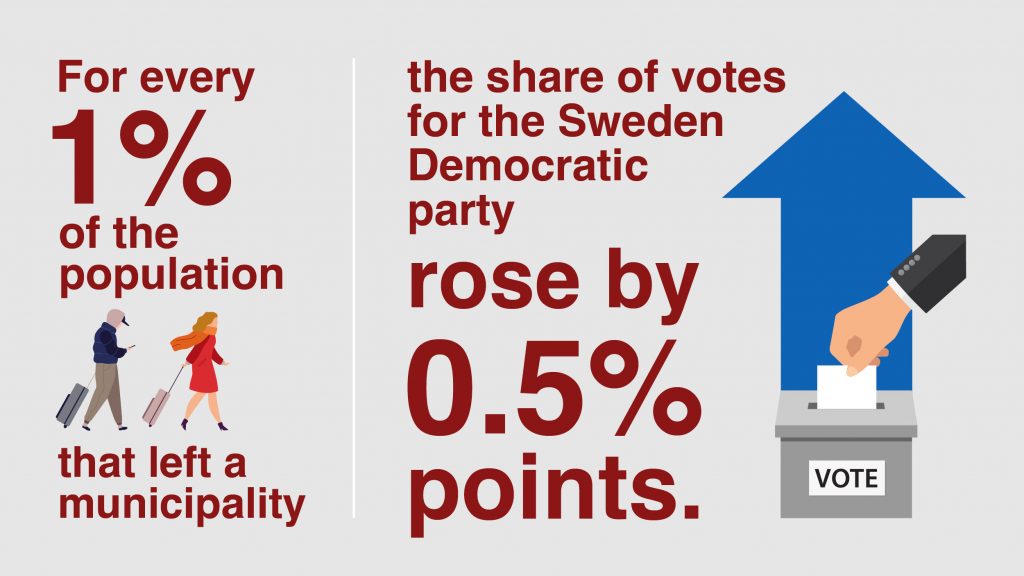

Looking at data over five election cycles from 2002 to 2018, the researchers found that for every 100 people who left a municipality (one percent of the population), the share of votes for the Sweden Democratic party rose by a half percentage point. While seemingly small, this is a significant gain for a party that held, on average, 8.3% of precinct votes during the study period. These gains came primarily at the expense of the Social Democrats.

Electorate Composition: Who is Left to Vote?

Why this trend? As high-income countries move towards postindustrial, service- and innovation-based economies, populations in peripheral regions are drawn to major urban centers. These migrating populations are more likely to be educated, economically secure, and open to interacting with the ethnically diverse populations found in cities—all attributes that research has shown make them less likely to vote for populist radical right parties. With the departure of this group of voters from sending communities, a greater share of the remaining electorate is likely to support populist radical right politicians.

Voting Preferences: Reduced Services Creates an Opportunity for the Right

However, emigration to urban centers does more than change who is voting in peripheral regions. It contributes to the deterioration of these regions, both in material and psychological terms, which in turn affects voter preferences. As young people leave for the cities, social services in sending communities are strained. Lacking a robust population to serve and sufficient tax base, local schools, hospitals, and businesses are forced to close. Public transportation dwindles. These impacts are clearly felt by those who remain: analyzing annual surveys of over 90% of Swedish municipalities from 2006-2018, the researchers found a strong negative relationship between emigration at the municipal level and residents’ satisfaction with local services.

To learn more about this dissatisfaction with the decline in the quality of public services, the research team looked at a random sample of 20 years of Swedish newspaper articles that focused on local out-migration, drilling down on those that discussed the political context. A majority (59%) of the articles noted a decline in local public services, including school and hospital closures, the lack of high-speed internet, and concerns about job availability. Many drew a link between these negative impacts and support for the Sweden Democratic party, as one journalist noted in an article following the 2018 election, “Voting for the Sweden Democrats can partly be seen as a protest against the deterioration of public goods and services–schools and healthcare—in the wake of emigration.”

Could the Social Democratic party have adopted a different strategy to avoid this outcome? Up to a point, perhaps. Interviews with party officials from both the Social Democrats and the Sweden Democrats revealed an awareness of how decades of growth strategies that drew skilled workers to urban centers contributed to local depopulation and service decline. However, Sweden’s proportional electoral system means that when voters move to big cities, so do parliamentary seats, essentially guaranteeing the very political neglect of depopulating areas that contributed to disillusionment with the Social Democratic party.

These material declines are compounded by a perceived loss of status as communities watch members leave for urban destinations. Discussing a municipality that lost over half its population, one party member described emigration to cities leading to “collective depression” among those left behind. Others said it created “a feeling of bitterness, everything revolves around Malmö, Gothenburg and Stockholm.”

Together, the decline in public services and loss of status cause frustration and disillusionment with the governing party. This creates a situation ripe for minority parties such as the Sweden Democrats to capitalize on, critiquing the incumbent party as out-of-touch and neglectful while positioning themselves as a fresh alternative, albeit without any clear plan to address rural decline.

While responding to these trends poses a complex challenge for policymakers, this research offers a powerful new lens for understanding how demographic shifts create political risks—with potential impacts for immigration, EU foreign policy, and climate change agreements.

What are the implications for politicians and party officials who want to avoid losing more ground to the far right? Center and center-left parties may feel pressure to address concerns about immigration and other cultural issues posed by the right. But moving towards a harsher stance on immigration to match the populist party stance or building a coalition with these parties could alienate much of their remaining base and may not be effective. The negative impacts of out-migration are not easily reversed, so once populist parties are in government, their promised easy fixes to address this difficult issue will likely not materialize, and their reliance on the protest vote may come to an end. Though more challenging, it may be better for centrist parties to refocus attention on the peripheral areas where their support is waning and address the decline in public services—and status—instead.

LOCATION

Europe, Sweden

RESEARCH QUESTION

What explains the recent rise in support for populist radical right parties in Europe?

TEAM

Rafaela Dancygier

Princeton University

Sirus Håfström Dehdari

Stockholm University

David D. Laitin

Stanford University, Immigration Policy Lab

Moritz Marbach

University College London

Kåre Vernby

Stockholm University

RESEARCH DESIGN

Difference in Differences

KEY FINDING

Emigration from small towns is an important driver of electoral support for populist radical right parties in Europe.