Anti-refugee protests in the streets. Arson attacks on refugee shelters. Public opinion hardening against refugees. As the Syrian civil war sent millions of people fleeing for safety abroad, backlash grew in countries across Europe and the United States.

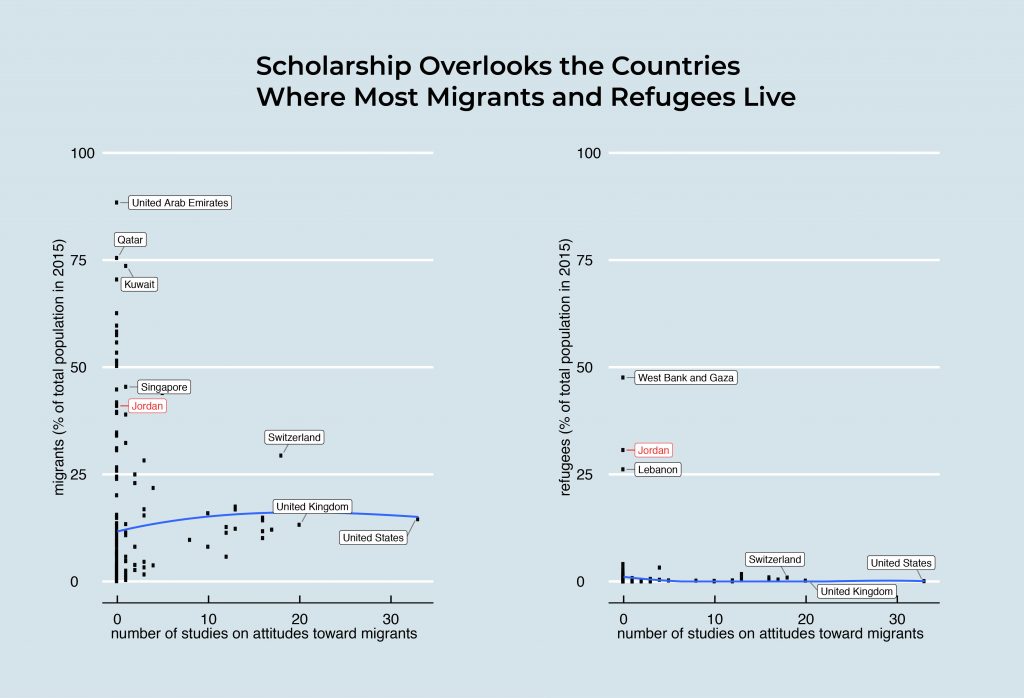

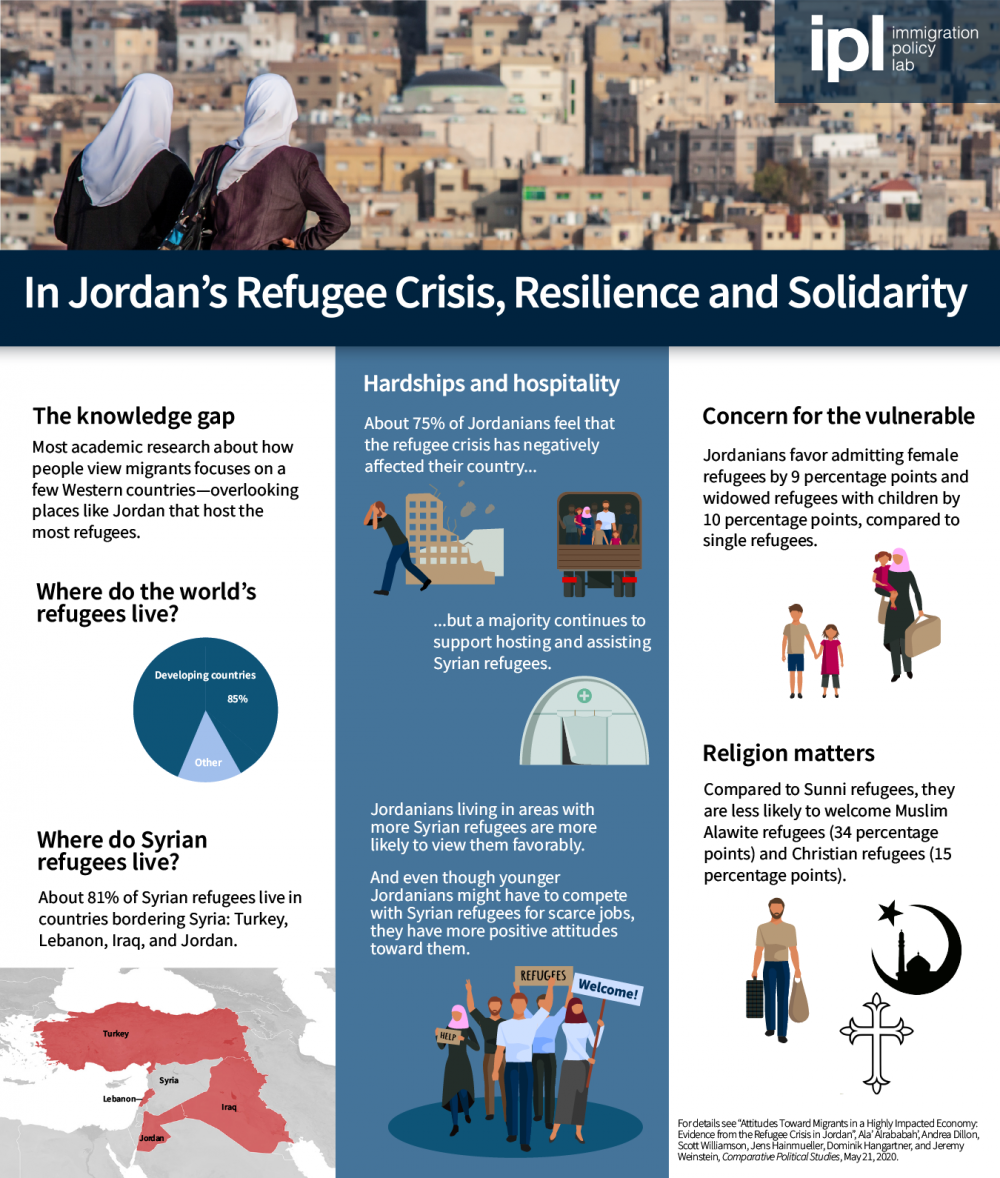

Rattled by this response, policymakers and researchers went looking for an explanation. They found some answers—worries about the expense of supporting refugees, or the influence of a foreign religion—but this effort has largely overlooked the developing countries where most Syrian refugees actually live. What is happening in places where they have arrived in much larger numbers, and where there are fewer resources to support them?

Consider Jordan, where Syrian refugees now make up more than 7 percent of the country’s population. Unlike in Europe, where most residents were personally unaffected by the refugee influx, in Jordan it has put substantial pressure on unemployment, public debt, and social services.

One might expect these hardships to foment public backlash against refugees, as happened in the West. But the dynamics in Jordan are much different, according to a nationally representative survey conducted by the Immigration Policy Lab (IPL) at Stanford University and ETH Zurich. Even as Jordanians acknowledged the difficulties stemming from the refugee influx, many remain committed to supporting refugees. Humanitarian sympathies, the researchers found, far outweigh economic concerns in shaping Jordanians’ attitudes and opinions regarding the country’s refugees.

The study should inspire a rethink of assumptions that emerged from research in Western countries, says co-author Ala’ Alrababa’h:

“A consensus had started to emerge about the drivers of attitudes toward immigrants and refugees, based on studies in Western countries. But there were reasons to question whether these findings would apply beyond the West, especially in countries where the number of refugees is often larger and where economic conditions are generally worse.”

Hardship and Hospitality

For policymakers working to support refugees, navigating public opinion is a key part of the puzzle. If locals are concerned about bread-and-butter issues, like competition for jobs or newcomers driving wages down, this points policymakers toward one set of possible remedies. If hostility to Islam is the sticking point, that sends them in an altogether different direction.

But if policymakers have to rely on anecdotes and guesswork to understand these dynamics, it’s much harder to make important predictions—like whether an influx of refugees will lead to conflict, or how much support there will be for humanitarian aid and integration programs. They need solid evidence.

Unfortunately, what we have learned comes mostly from research focused on Europe and the United States, where local economies are strong, social services are extensive, and there are cultural differences between residents and refugees.

For the IPL researchers, Jordan presented an ideal contrast to begin correcting this bias. It has high unemployment, especially among younger adults; its social services were under strain even before the refugee crisis; and most of the Syrian newcomers share Jordan’s culture, language, and dominant religion. The team surveyed 1,500 Jordanians, asking them how they think refugees have affected their country, how they feel about the refugees themselves, and whether they wanted Jordan to scale back its support for refugees.

Since even people in prosperous Western countries tend to focus on refugees’ use of public services or the cost to taxpayers, the researchers expected to encounter even greater concern in Jordan. After Syrians began arriving in 2011, Jordan’s unemployment rate rose from 14.5 to 22 percent. Housing prices went up by 300 percent in 2013 alone. And by 2017, there were about 100,000 Syrian children in the country’s public schools. Unsurprisingly, then, Jordanian survey respondents did say that the refugees had negatively affected the country’s economy, housing, education, and more.

But this overwhelming consensus made other findings all the more remarkable. Most Jordanians supported hosting refugees and opposed policies that would harm them. And Jordanians more likely to experience the economic strain of the refugee crisis were even more sympathetic:

- Younger respondents held more positive attitudes toward refugees in Jordan, despite their higher unemployment rates.

- Those more likely to work in the private sector rather than for the government held more positive attitudes toward refugees, despite their greater vulnerability to job competition from Syrians.

- Those who had more contact with refugees and who live in areas with greater numbers of refugees held more positive attitudes toward them.

This isn’t what one would expect if members of the host community mainly worry about negative consequences for themselves, says study co-author Scott Williamson:

“We were surprised to find that economic concerns are not a significant driver of attitudes. Given the economic difficulties Jordan faces, it would make sense to find greater hostility toward refugees among vulnerable Jordanians whose communities have been directly affected by this crisis. Yet the opposite is the case.”

The Role of Culture

The researchers also asked respondents to compare pairs of refugee profiles and choose the one whom they preferred to be admitted to Jordan. Each profile included a random mix of nine characteristics, including level of education, religion, previous occupation, and the reason the refugee fled Syria. The researchers designed this exercise to measure how people weigh economic, cultural, and humanitarian values when determining their level of support for hosting refugees.

Again, economic factors didn’t seem to influence respondents’ choices. They did prioritize refugees who would be self-reliant and who had been employed in Syria, but not by much. They didn’t favor refugees in skilled professions (accountant, engineer) over less skilled ones (barber, farmer). And they preferred to host refugees with greater vulnerability, such as widows with children or elderly people.

Meanwhile, one might expect that cultural considerations wouldn’t weigh heavily in respondents’ decisions, since Syrians and Jordanians have much in common culturally. Cultural differences, however, were massively influential, as in Western contexts. The vast majority of Syrian refugees in Jordan are Sunnis, though as of 2014, around 20,000 Syrian Christians had entered Jordan. The number of Alawite refugees in Jordan is likely minuscule.

Across all refugee profiles, by far the most penalized were those from a minority religious group:

- Alawites were 34 percentage points less likely to be admitted than Sunnis.

- Christians were 15 points less likely to be admitted than Sunnis.

- Even Sunni respondents who reported being the least religious still penalized outgroup religions.

At the same time, cultural similarities were powerful in encouraging generosity. When the researchers asked focus group participants to explain why they remained committed to supporting Syrians despite the economic hardships involved, they spoke of “shared history” and the feeling that, “as Muslims, we can’t let [fellow Muslims] down.” As one participant put it, “They can come in; even if I don’t have enough to eat and my girls don’t have enough to eat. . . . I, as a Muslim, am obliged to open the door for my brother.”

These insights from Jordan should encourage policymakers around the world to reconsider some of the ways they attempt to increase their population’s support for hosting refugees. For example, in outreach campaigns and political rhetoric, we often hear that refugees benefit the economy or that they become self-sufficient in time. But one lesson from Jordan is that these economic messages may be less necessary in certain contexts than we think. A more impactful approach could be to help the public see refugees as similar to themselves—for example, in terms of common values or the shared hardships of war. When policymakers tap into the public’s reservoir of goodwill and humanitarian concern, residents of the host country can, as in Jordan, be invaluable allies in the effort to support refugees.

LOCATION

Jordan

RESEARCH QUESTION

What factors shape attitudes toward refugees in developing countries?

TEAM

Ala’ Alrababa’h

Andrea Dillon

Scott Williamson

Jens Hainmueller

Dominik Hangartner

Jeremy Weinstein

RESEARCH DESIGN

Nationally representative survey and conjoint experiment

KEY STAT

Developing countries host 85 percent of the world’s 25.4 million refugees