Temporary Protected Status (TPS) has protected nearly one million immigrants—yet we know little about its impact

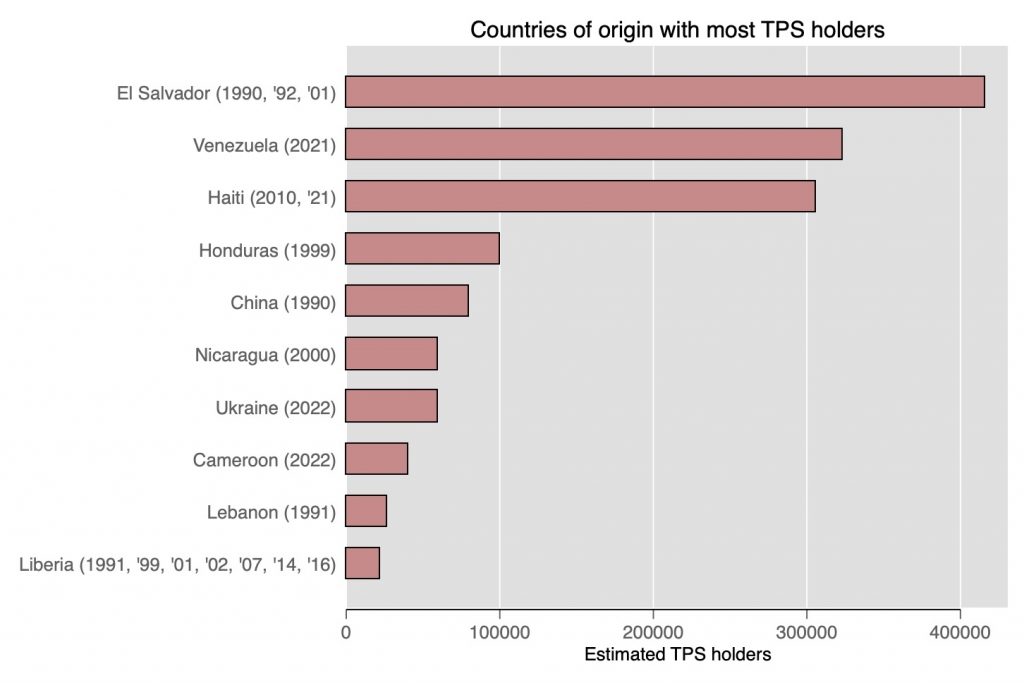

Nearly 875,000 immigrants have been granted the freedom to live and work in the United States thanks to a humanitarian program called Temporary Protected Status (TPS). In place since 1990, TPS allows the Secretary of Homeland Security to prevent certain immigrants from being deported if their home country has become too unsafe for return. This designation includes 14 countries at the time of this writing, and the Biden administration would like to expand the program and provide a pathway to citizenship for TPS holders.

But even though TPS is one of the largest humanitarian programs in the U.S. immigration system, we know almost nothing about its effects on individuals, their families, and the communities where they live. Now, IPL researchers offer a new dataset and research methods to help uncover insights into the program’s impact. Here, program manager Elisa Cascardi walks us through the program’s origins and controversies and explains how IPL is working to measure the wide-ranging effects of TPS.

Q: Among all the immigration issues that attract political debate, TPS is perhaps a lesser known or misunderstood program. Why is it important to understand how TPS changes peoples’ lives? How would this knowledge be useful for policymakers?

Elisa Cascardi: We have seen suggestive evidence that TPS is positively associated with increased employment and higher wages, but we haven’t been able to establish causality at a large scale. Our goal is to measure the extent to which TPS holders benefit from the policy, looking at all the countries included in the program. This type of research helps policymakers understand how offering legal status affects immigrants’ lives—by quantifying those effects, we can better inform important policy decisions.

Q: In addition to wages and employment rates, are there any other outcomes researchers and policymakers should consider? What are some other ways a person’s life changes with the move from unauthorized status to a protected status?

EC: We take a fairly comprehensive approach to this question in our research. We have looked at whether TPS helps people move above the poverty line, as well as the types of public benefits someone receives, including health insurance. We also look at intergenerational effects. Do children become more likely to remain in school or complete more years of schooling when their parent receives TPS? We’d also like to identify whether TPS gives people access to other forms of legal status that offer greater benefits. How many people exit the program, and what paths do they take?

Q: How would you frame the debate around the policy? It seems like TPS has attracted criticism both from those who want to restrict immigration and those who want to facilitate it. What are some of these criticisms?

EC: The policy itself has not changed much since the time it was first implemented, but the reactions to it have changed along with the politics surrounding immigration. What has been most debated is the temporality of the policy—TPS is initially allowed for 18 months at most, but it often is extended beyond that period. The average TPS holder has lived in the United States for twenty years. So we aren’t using the policy instrument in the way it was originally designed.

When expiration dates come up, people may be at risk of deportation and may lack a foundation to restart their lives in the country they left. Designations are extended when the unsafe conditions still exist. However, over time those conditions may end, and new ones arise. When designations are terminated because initial conditions subside, these new conditions may not be assessed and the policy won’t be newly designated. This can leave individuals at risk of being deported to an unsafe place.

Recently, TPS was in the news because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people who entered the United States without a valid visa can’t apply for lawful permanent residency. While people may be eligible for TPS because they arrived before the designation date, the majority of TPS holders entered without a valid visa, so this new ruling closes a path to permanent residency for them. Unfortunately, this ruling does not take into account the overwhelming reality for many seeking humanitarian protection: when fleeing a catastrophe, people often have limited means to move lawfully.

Q: Have any reforms or alternative policies been proposed?

EC: Some people have suggested that the policy should only be implemented temporarily, meaning that country designations should not be renewed. Others have suggested that, because the policy is temporary, creating paths to permanent residency and citizenship for TPS holders is necessary to ensure their long-term safety. And others would like to directly legalize this population, as happened with the Gulf War TPS designates and certain TPS holders under the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act of 1997.

Another area for reform is the designation timing. A country’s designation—the effective date when it allows individuals to be protected—is always retroactive under TPS. Additionally, it is usually implemented at the onset of a crisis, leaving many without protection who come as the crisis persists. There are advocates who would prefer a rolling enrollment, so that people who continue to arrive throughout the duration of crisis can be protected. For example, South Sudan was recently redesignated for the first time since 2016. So all those who came to the United States after 2016 have been living without protection. With the redesignation, we see people coming forward to take advantage of the policy who were previously here without legal status.

Uncovering Insights into TPS

Q: It seems natural that researchers and policymakers would want to know how people fare after they’re enrolled in the program. Why is this difficult to study? What approaches have they tried, and what were the pitfalls?

EC: The first obstacle is that we don’t have publicly available data that identifies people who have received TPS. In a way, this is actually a great thing. It’s good that we can’t easily access detailed information about people from unsafe countries, who may have fled persecution. But this lack of data makes it difficult to discern what services and programs TPS holders might need. To overcome this, we could create a survey and recruit people we think might have TPS. But this might risk compromising their anonymity and privacy, and it would be expensive and time-consuming.

The second challenge is identifying a control group for comparison. Just as we lack data on people enrolled in the program, we also lack data on people who look very similar but do not have TPS. It’s also an open question whether you can meaningfully compare people who come from different countries. They may be similar across many characteristics, but the difference in country of origin might be consequential.

Q: One of the first things you did in this project, working with your colleague Vasil Yasenov, was to create a policy dataset that gathers all the TPS country designations since the beginning of the program. Why was this a necessary first step?

EC: We wanted to determine the effects TPS has had on all program participants since its inception. To do that, we first needed to know all the TPS policies that had been implemented and when they were active. There was no central database to tell us which countries historically were designated and why, how many people they covered and during which time periods. DHS issues formal declarations whenever a country is designated for TPS or has its designation suspended. Those only exist in federal registers, which are public notices of various governmental agencies’ decisions.

Once we could see who was eligible or not based on their year of arrival, we could then use the American Community Survey (ACS) to match people to those years of eligibility. The ACS, a survey program run by the US Census Bureau, asks respondents how many years they’ve lived in the country.

Q: Other researchers have used the ACS to make inferences about the TPS population. What did you do differently?

EC: Others have studied a particular group of TPS recipients from a single country, but they couldn’t extrapolate from one group’s experience to say something definitive about the policy itself. Unlike other studies, we tried to identify comparison groups that were more closely aligned with the treatment group, the TPS holders. We came up with a few different ways of doing this and conducted validation exercises to see which control groups were the most similar.

Q: Did any of the results surprise you? What were you expecting to find?

EC: What’s most surprising is that across all countries, we see very different results. I expected to see trends, but the outcomes were divergent. That doesn’t tell us that the policy isn’t beneficial, but it does suggest that the data is insufficient to answer the question.

Q: If we could wave the proverbial magic wand and remove these obstacles in data availability and research design, what would you most want to know about TPS holders and the broader group of people living in the United States without legal status?

EC: I think it would be immensely valuable to identify the value of legal status. I think this likely goes beyond protection from deportation and access to work permits. These are building blocks of life that in turn enable other things, like health or education, that help people thrive. So I’d like to better understand how offering even basic, modest protections can lead to an outsized impact on those people and their family members. We’ve only just begun to measure how the threat of being deported affects someone’s health, for example. What about buying property, getting a car, opening a bank account? How much more precarious is a person’s life when he or she lacks legal status and is unable to work legally, receive public benefits, or enroll children in school?

Q: If you could somehow change the TPS program yourself, what change would you make?

EC: The process behind the country designations is opaque and left up to the political leanings of the day. I think the program should have a more transparent set of criteria for assessing country designations, redesignations, and terminations. This will, in turn, ensure the policy is implemented as it was designed and be more accountable to the people it seeks to protect.

Elisa Cascardi is a program manager at the Immigration Policy Lab. She manages IPL’s portfolio of projects related to legal services and public health policies for refugees and immigrants in the United States.