What do you think of when you hear the word “refugee”? For many people, what comes to mind is vulnerability—you might imagine the grim conditions of a refugee camp or the dangers of the desperate journey to safety. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that refugees are widely perceived to be especially needy or dependent on public assistance.

But in their search for opportunity and community, refugees in the United States actually look just as resourceful as other immigrants. That’s according to an IPL study from researchers at Stanford, Dartmouth, and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Immigration Statistics (OIS).

As they build a new life in the country, many refugees move to a different state soon after arrival, according to a new dataset on nearly 450,000 people who were resettled between 2000 and 2014. And when they move, they are primarily looking for better job markets and helpful social networks of others from their home country—not more generous welfare benefits.

“These findings counter the stereotype that refugees are destined to become a drain on state resources over the long run,” says study co-author Jeremy Ferwerda. “When choosing where to live in the United States, refugees do not move to states where welfare benefits are highest. Instead, they leave states with high unemployment rates and move to states with booming economies and employment opportunities. ”

Harnessing the Data

Part of the reason we haven’t had a clear picture of refugees’ lives in the United States is that it isn’t easy to connect different data sets in a way that allows you to follow each refugee over time. The U.S. Department of State keeps the records on new arrivals, including their country of origin, education, and ties to family or friends already living here. Records of milestones in their integration process, including becoming legal permanent residents and, later, citizens, are the province of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Making this information useful calls for new partnerships between researchers and government agencies. “We are grateful to the Office of Immigration Statistics for providing this invaluable opportunity for collaboration between IPL and OIS researchers,” says Duncan Lawrence, IPL executive director and study co-author. “This work would not have been possible without this partnership and input from knowledgeable, dedicated leaders in this office.”

Before this, researchers have had to use small samples, either fielding a survey that asks people whether they entered the country as refugees, or using existing surveys and guessing at refugee status. Now, the IPL team had a sample of unprecedented size, accuracy, and detail.

“The law suggests that secondary migration should be monitored to help inform policymaking,” says IPL co-director and study co-author Jens Hainmueller. “Our study helps with that, since we have captured secondary migration for the full population, for the first time.”

Push And Pull Factors

One of the first things the researchers wanted to know was where refugees were living. U.S. refugee resettlement agencies assign each incoming refugee to a particular place, and their local offices receive federal funding to help the newcomers get settled. Until now, we haven’t known how many of them leave their assigned location or what motivates them to move.

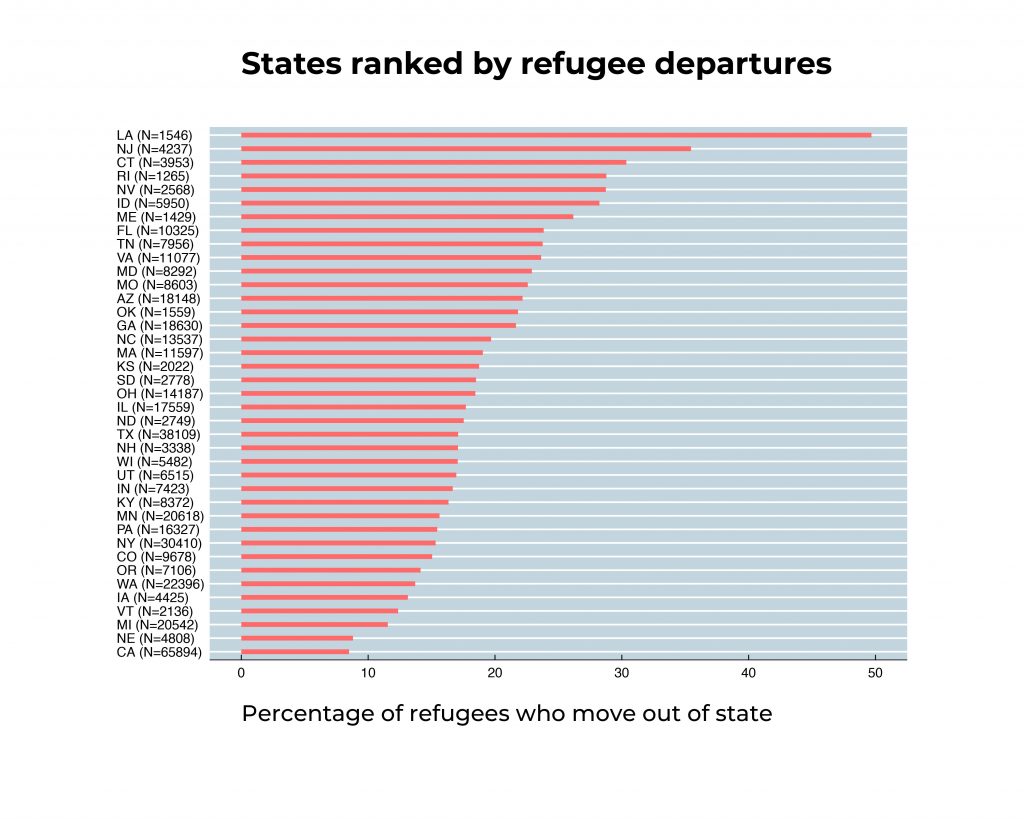

Because refugees are required to apply for permanent resident status a year after arrival, the researchers could note how many had a different address by then, and the numbers were surprising. Of the 447,747 refugees they observed, 17 percent had moved to a different state around the one-year mark. For other non-citizens during the same period, only an estimated 3.4 percent move out of state within the same time period after arrival.

Not only were the refugees highly mobile; there were distinct patterns in their movement. Some states were much more likely than others to see their refugees leave. In Louisiana, New Jersey, and Connecticut, more than 30 percent of refugees quickly relocated, while in California and Nebraska, only 10 percent did. Midwestern states had the greatest gain in refugees from other states, with Minnesota receiving the most.

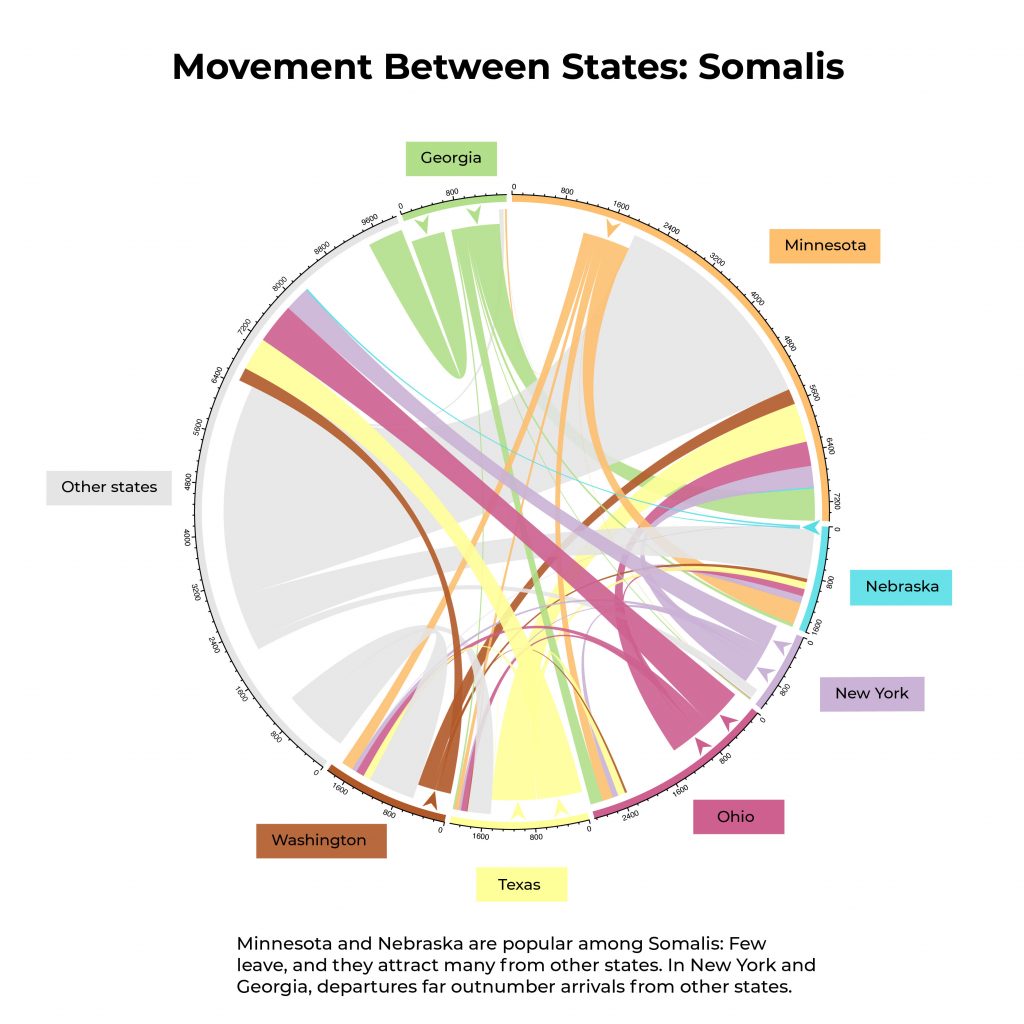

With information on so many refugees, the researchers also were able to uncover patterns among people from the same country. Those from Somalia and Ethiopia left their assigned states in the greatest numbers. Congolese refugees, who were among the most likely to stay put, were 34 percentage points less likely to move than Somalis.

With information on so many refugees, the researchers also were able to uncover patterns among people from the same country. Those from Somalia and Ethiopia left their assigned states in the greatest numbers. Congolese refugees, who were among the most likely to stay put, were 34 percentage points less likely to move than Somalis.

So what were the refugees looking for in a home? To find out, the researchers looked at the states in pairs and counted the number of arrivals and departures on each side. The greatest movement happened between state pairs that had the greatest difference in the share of the population who were from a refugee’s home country. In other words, states where co-nationals are a higher share of the population tended to receive refugees from states with a lower share, and the numbers increase as the gap between the two states widens.

Economic opportunity was another strong pull factor. Refugees were especially likely to leave states with high unemployment in favor of states with low unemployment. Housing costs were another factor, though their influence was not as strong.

These findings echo research on migration patterns among recent immigrants, who have settled in different places than the traditional destinations that attracted earlier waves of newcomers. Immigrants as a whole highly value places that offer them a chance to make a good living and establish a supportive community—and refugees are no different.

These findings echo research on migration patterns among recent immigrants, who have settled in different places than the traditional destinations that attracted earlier waves of newcomers. Immigrants as a whole highly value places that offer them a chance to make a good living and establish a supportive community—and refugees are no different.

U.S. refugees do stand out from other immigrants in at least one way: In an earlier study using the same dataset, the researchers found that they become citizens at much higher rates. Among refugees who arrived between 2000 and 2010, 66 percent had become citizens by 2015. And here again, opportunity, community, and place make a difference. Refugees placed in urban areas with lower unemployment and a larger share of co-nationals were more likely to naturalize.

Making a Better Match

Overall, these findings suggest that the U.S. refugee resettlement system is working relatively well, since most refugees do stay and build new lives in the places where they are sent. Still, one might look at all this movement and lament a certain inefficiency: The system devotes resources to helping refuges get situated in a given place, and they don’t travel with the refugees who move.

So there’s plenty of room to improve the match between refugees and local destinations, and the IPL team has a solution to offer: a data-driven tool called GeoMatch that makes personalized location recommendations for each refugee. The tool can also help economic immigrants decide where to live within a new country. For both groups, it puts vast amounts of previously unused data to good use, informing decisions that can alter the course of people’s lives.

LOCATION

United States

RESEARCH QUESTION

When resettled refugees move away from their assigned location, what motivates them?

TEAM

Nadwa Mossad

Jeremy Ferwerda

Duncan Lawrence

Jeremy Weinstein

Jens Hainmueller

RESEARCH DESIGN

Administrative Data Merge

KEY STAT

17 percent of resettled refugees in the United States moved to a different state within a year of arrival