Administrative records provide little evidence that immigrants engage in “welfare migration” in Switzerland

Immigrants’ use of welfare services has been a contentious issue in countries across the world. One narrative, known as the “welfare magnet” hypothesis, suggests that many immigrants deliberately choose to live in regions with generous welfare benefits.

Policymakers have frequently relied on this hypothesis to justify reforms to welfare policy that cut benefit levels for immigrants or tighten eligibility requirements. It has also impacted politics, with parties frequently leveraging the prospect of “benefit tourism” to mobilize voters.

Given the consequences of these ideas, it is critical to understand whether welfare migration actually occurs and to what extent. Although claims of widespread “benefit tourism” should be viewed with caution, the expectation that benefits will play some role in shaping immigrants’ residential decisions is theoretically well established. As first formulated in a seminal study by Charles Tiebout in 1956, we should expect people to “vote with their feet” and select a residential location that maximizes economic gains. This behavior may be particularly pronounced among immigrants, which may have less extensive social and labor market networks than citizens, reducing the potential costs of relocation. They might also be more economically vulnerable than citizens, particularly during the first years after arrival, and thus may rely more on social safety nets.

Despite the theoretical consensus, the actual evidence for welfare migration remains mixed. While some studies have found that immigrants tend to concentrate in specific regions with generous welfare benefits, others suggest that immigrants tend to prioritize employment or coethnic networks over welfare considerations when choosing where to live within destination countries.

Which argument finds more support in the data? A new study from the Immigration Policy Lab (IPL) involving researchers from Dartmouth College, University College London, and ETH Zurich empirically assesses the prevalence of subnational welfare migration. Looking at ten years of administrative records covering all social assistance recipients in Switzerland, IPL researchers found limited evidence that immigrants who relocate substantially increase their welfare income. In addition, they found that municipalities that increase benefits do not attract more immigrants.

Testing the welfare magnet hypothesis

The ambiguity of existing research on the welfare magnet hypothesis is linked to data availability and research design issues. First, while many studies on the welfare hypothesis rely on data measuring the rate of movement by immigrants, they usually don’t have data on whether these immigrants apply for welfare after relocating. Without this key piece of information, it is difficult to determine whether immigrants are actually engaged in welfare migration. Second, locations with generous welfare benefits might also be attractive for other reasons. Jeremy Ferwerda, assistant professor of political science at Dartmouth College, explained the conundrum: “high welfare benefits may be related to other factors, such as economic prosperity, cost of living, or the size of the immigrant community, which can influence where immigrants decide to relocate. This makes it difficult to isolate the actual relationship between benefit levels and immigrants’ residential choices.”

IPL researchers found a way to address these issues by focusing on internal migration in Switzerland. Their study relies on detailed administrative data covering the entire population of social assistance recipients over the 2005 to 2015 period. Switzerland’s decentralized system of welfare provision leads to high variation in benefit levels for social assistance. In addition, the country’s small geographic distances, sizable immigrant population, and limited barriers to movement imply that Switzerland is a likely case for welfare migration. To test the hypothesis, the researchers studied immigrants’ reactions to changes in social assistance rates due to the introduction of standardized guidelines for social assistance (known as the SKOS guidelines) at the cantonal level. The researchers compared immigrants’ probability to move to or from municipalities that introduced (or repealed) standardized social assistance levels to the relocation choices of otherwise similar immigrants living in comparable places that did not introduce such standardized levels.

Little evidence for welfare migration

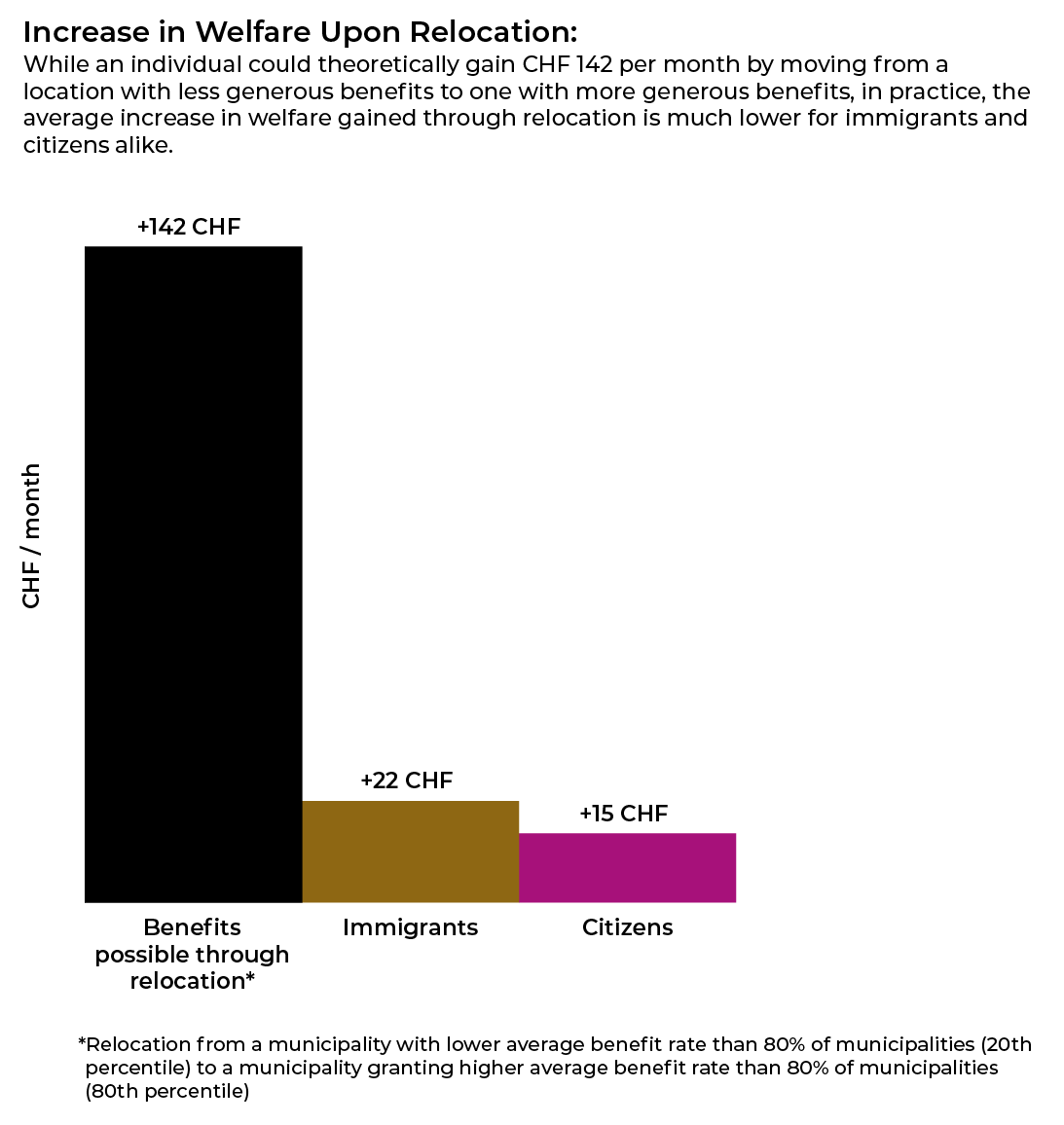

The researchers first looked at average migration rates among welfare recipients. They found that welfare recipients are relatively mobile: in a typical year, approximately 7.8 percent of Swiss beneficiaries relocate and receive benefits from a new municipality. Despite frequent media coverage surrounding immigrant “benefit tourism,” the annual inter-municipality relocation rates of immigrant beneficiaries is consistently lower, at 5.2 percent. Second, the researchers compared the potential gains from welfare-maximizing relocations to the actual increase in welfare income among recipients who moved. If they moved from a municipality with lower benefit rates than 80 percent of municipalities (20th percentile) to a municipality with higher benefit rates than 80 percent of municipalities (80th percentile), recipients could theoretically increase their welfare income by CHF 142 per month (about 153 USD). Compared to this benchmark, actual changes in welfare income are relatively minor. While Swiss citizens, on average, increase their welfare income by CHF 15 (16 USD) per month after moving, this increase is only slightly larger for immigrants, at CHF 22 (24 USD) per month.

The researchers also estimated the expected inflow of welfare recipients following an increase in benefit rates. They find that a municipality with 10,000 residents that increases the monthly benefit rate by CHF 100 (108 USD) could expect to receive 1.2 additional citizen beneficiaries each year. However, the same shift in benefit rates does not attract additional immigrants. Summarizing the evidence, Moritz Marbach, associate professor of public policy and data science at the University College London, said: “Our different analyses provide a consistent finding: On average, the immigrant population in Switzerland does not engage in meaningful welfare migration.” These findings complement evidence from another IPL study in the United States. In that study, researchers looked at 208,060 immigrants living in the U.S. between 2000 and 2016 during an expansion of healthcare coverage for children and pregnant women, and found no evidence that immigrants moved to places with increased benefits.

What factors shape immigrants’ relocation choices, if not benefit rates? In an additional analysis, the researchers found that immigrant welfare recipients are likely to move to larger municipalities, those with lower housing costs and more extensive co-ethnic networks. Dominik Hangartner, professor of public policy at ETH Zurich, said: “The results suggest that immigrants carefully select their destinations but based on factors beyond marginal changes in welfare benefits. In light of this finding, claims of subnational ‘benefit tourism’ seem exaggerated.” Despite the lack of evidence, these claims often have direct policy consequences, as governments have cut benefit levels or restricted eligibility to discourage presumed welfare migration. For policymakers interested in stabilizing welfare provision in diversifying societies, IPL’s research suggests that such anticipatory cuts are neither necessary nor useful to deter welfare migration.

LOCATION

Switzerland

RESEARCH QUESTION

Do welfare benefits determine where immigrants move?

TEAM

Jeremy Ferwerda

Moritz Marbach

Dominik Hangartner

RESEARCH DESIGN

Administrative Data Merge

KEY STAT

Approximately 7.8% of Swiss beneficiaries relocate and receive benefits from a new municipality in a given year, compared with 5.2% of immigrant beneficiaries.

FUNDERS

European Research Council (ERC)