When the “nudge” first appeared on the policymaking scene, it struck many as an ideal tool. Unlike traditional interventions aiming to improve people’s behavior, a nudge is low-cost, non-coercive, and less likely to have unintended consequences. More than a decade later, though, nudge enthusiasts readily admit that designing an effective nudge isn’t easy.

For one thing, nudges often are aimed at people who are difficult to engage: those living with hardships like poverty, disability, or limited English proficiency. The stress associated with socioeconomic disadvantages can complicate their efforts to make positive choices and plan for the long term, so nudges that create an encouraging “choice architecture” are welcome. But even where people are motivated to pursue a certain goal, it’s hard to craft a nudge when you don’t know what’s getting in their way.

Take citizenship, for example. Most immigrants in the United States, when asked, say they want to become citizens, yet naturalization rates are surprisingly low compared to those of other Western countries. Many organizations devote themselves to promoting citizenship, especially among low-income immigrants, but they can’t say for sure whether their campaigns are actually working.

It’s just the sort of social pattern where a nudge could make a big difference, if done right. And according to a new study from the Immigration Policy Lab (IPL) at Stanford University, the answer turns out to be the gentlest kind of nudge: simple, well-placed information.

An Untapped Resource

The IPL researchers had been studying the citizenship puzzle, looking to better understand the barriers that keep low-income immigrants from applying. To explore these questions, they partnered with New York’s Office for New Americans to evaluate NaturalizeNY, a program providing financial and logistical help with the naturalization process.

Along the way, the researchers noticed that the poorest immigrants who registered for the program weren’t taking advantage of a federal program that would allow them to apply for free. Currently, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) will waive the $725 application fee for those who live below 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or receive means-tested benefits like food stamps, welfare, or Medicaid. The NaturalizeNY study had revealed that hefty fee to be a decisive deterrent, even when immigrants are highly motivated to apply. So why leave that benefit unclaimed?

What the researchers noticed in New York is just as conspicuous nationwide. Of the 9 million immigrants who are eligible for citizenship but haven’t applied, almost half could be eligible for the fee waiver. Yet only about 20 percent of citizenship applications come with a fee waiver request, according to data from 2013–2016.

A likely culprit, the IPL team thought, is lack of information. It isn’t easy to find out about the program if you aren’t determined—combing through government websites or seeking help from an immigration lawyer or nonprofit. All of that takes time and energy, and people struggling to get by may not have much to spare.

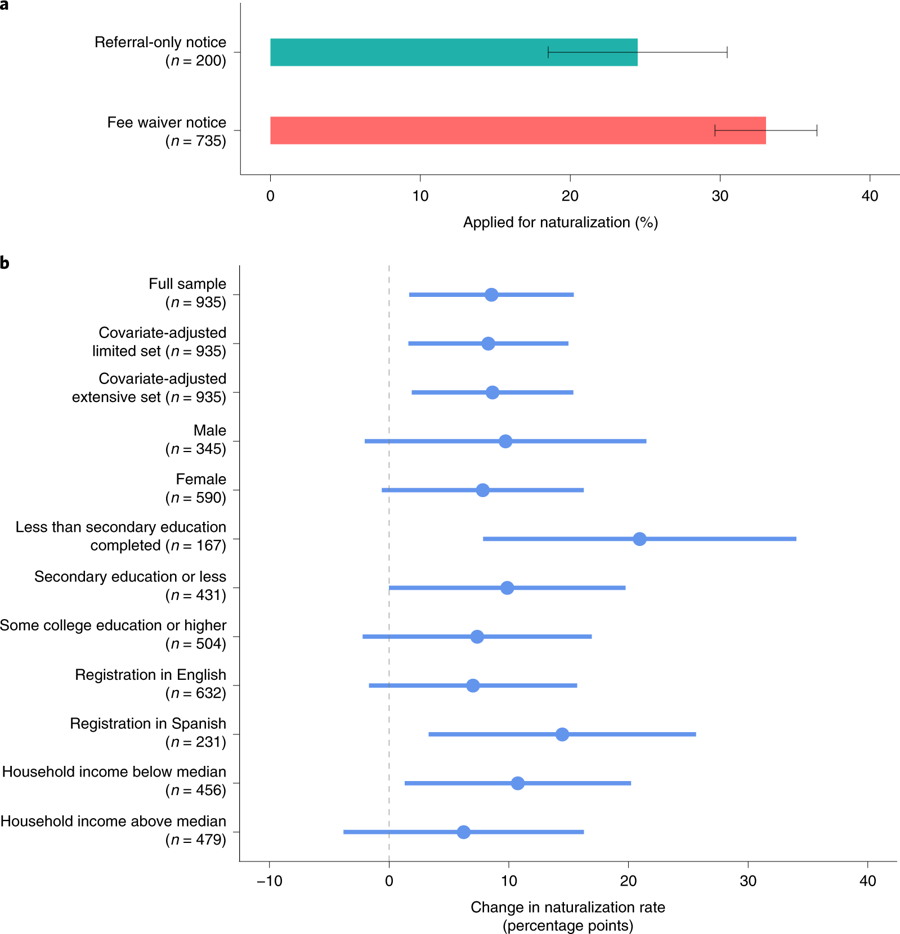

To test this theory, the researchers identified 1,537 NaturalizeNY participants who were likely eligible for the fee waiver. For 75 percent of them, the online registration form ended with a notice informing them of the fee waiver alongside a link to information on where they could receive application assistance. The other 25 percent saw only the link to the application assistance. (Ultimately, they too were informed.)

Four months after the registration ended, the researchers checked in to ask whether they had applied for citizenship. The unadorned message tucked into the registration system had made an impression: immigrants who saw it were 35 percent more likely to apply for citizenship than those who didn’t.

Looking deeper into the results, researchers wanted to know whether their nudge, if scaled up, would boost citizenship rates or just make the fee waiver program more expensive as people who would have applied anyway increasingly did so for free. Was the fee waiver really inspiring new people to become citizens, or just helping existing applicants save money? They found that for every six immigrants who applied only because the fee waiver made it affordable, 1.5 merely switched from paying the fee to claiming the benefit.

The researchers were intrigued to find that the nudge was most effective for those who were less educated, had lower incomes, and registered in a language other than English. While it boosted citizenship applications by 8 percentage points overall—from 25 to 33 percent—the gain was 21 percentage points among immigrants with no high school diploma, for example, compared to only 7.4 percentage points among those with at least some college education.

“Previous research on other benefits programs has shown that the increase in usage may be concentrated among those with fewest barriers. In this case, the information helped those who might be considered to be most in need of assistance,” said Michael Hotard, program manager at IPL and one of the study’s authors.

Paving the Way to Citizenship

If you think about the ways these disadvantages limit people’s capacity to tackle important, long-term life goals like citizenship, it seems striking that the most “bandwidth compromised” immigrants were the most likely to respond to the nudge. The findings suggest that the people who need the fee waiver the most were the least likely to know about it. And that plays into the broader concern that government programs for the needy are too burdensome in expecting their intended beneficiaries to navigate a bureaucratic labyrinth just to discover the program, let alone figure out whether they qualify and how to apply.

And while the IPL study suggests that the fee waiver program can be critical for low-income immigrants’ ability to become citizens, it may soon become more burdensome to access. USCIS is moving to eliminate the presumption that receiving means-tested benefits qualifies an applicant for the fee waiver. This will exclude some immigrants from the program altogether, while the rest will face a more complicated process to prove that their incomes fall below 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines.

But if the country wants to raise its naturalization rates and promote citizenship as a catalyst for immigrants’ integration and social mobility, the IPL study suggests that the USCIS reform is taking the fee waiver program in the wrong direction. Instead, it could undertake information campaigns to spread the word and introduce a tiered, progressive fee structure to make up for any lost revenue as more people claim the waiver.

Barring that, the IPL team says, states are well positioned to act on the findings. Since states administer many means-tested benefits, they can use enrollees’ information to identify immigrants whose incomes meet the eligibility requirements for the fee waiver and experiment with various forms of outreach to let them know about it.

The USCIS-proposed changes drew a wave of public comments from immigrant service providers urging the agency to reconsider. With their commitment and the new IPL evidence, states inclined to facilitate naturalization and enrich their communities would have a good place to start, simply by providing more information about the fee waiver.

LOCATION

United States

RESEARCH QUESTION

How can low-income immigrants be encouraged to apply for citizenship?

RESEARCH DESIGN

Randomized Control Trial

KEY STAT

Of the 9 million immigrants eligible for U.S. citizenship, about half qualify for the federal fee waiver

TEAM

Michael Hotard

Duncan Lawrence

David D. Laitin

Jens Hainmueller

FUNDERS

Robin Hood

New York Community Trust