As refugee flows have increased around the world, many governments are grappling with acute political pressure along with the logistical challenges of supporting refugees and processing asylum applications. Perhaps most notably in Europe, where populist and other opposition parties have seized on the refugee crisis, leaders are pulled in two different directions as they seek both political self-preservation and practical solutions. Policies that resolve political conflict in the short term, on the one hand, tend not to serve refugees’ long-term integration, on the other. All too often, these compromises backfire, undermining the country’s ability to successfully integrate refugees—and leading to higher social and economic costs in the long run.

Policies surrounding refugee employment are a good example of this dynamic. Locking them out of the labor market may subdue backlash from constituents who worry about facing competition for jobs, or who want to discourage refugees from entering the country and remaining there indefinitely. But it also leaves them dependent on the government, unable to pay taxes, and poorly positioned to find work when their asylum applications are finally approved after a long, idle wait.

Policies surrounding refugee employment are a good example of this dynamic. Locking them out of the labor market may subdue backlash from constituents who worry about facing competition for jobs, or who want to discourage refugees from entering the country and remaining there indefinitely. But it also leaves them dependent on the government, unable to pay taxes, and poorly positioned to find work when their asylum applications are finally approved after a long, idle wait.

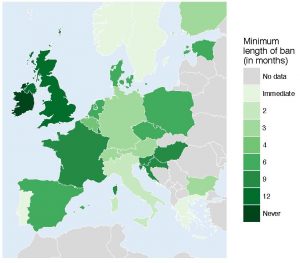

Yet most EU countries take this route, barring refugees from working for a period of time after arrival. What does it cost them? According to IPL research, governments that impose these temporary “employment bans” are paying a higher price than they realize.

Measuring the Costs

At a time when the European Union is embroiled in debate about the future of its recently arrived refugee population, one might think there would be keen interest in encouraging refugees to become self-sufficient as soon as possible. In practice, however, the Continent’s rough consensus in favor of employment bans persists, in part because their detrimental effects are difficult to measure.

First, much of the available historical data doesn’t allow researchers to readily distinguish people who entered a country as asylum seekers from the general inflow of immigrants. Second, it’s tricky to isolate the employment ban from the many other factors that influence whether refugees struggle or thrive. If refugees fare better in a country with a shorter employment ban or none at all, the reason could be any number of differences that make its labor market or asylum policies more hospitable than those of other countries. If refugees within a country have greater difficulty finding a job after a temporary employment ban is imposed, perhaps the ban itself is to blame, but that can be hard to prove if, say, there was also a downturn in a particular work sector well suited to refugees.

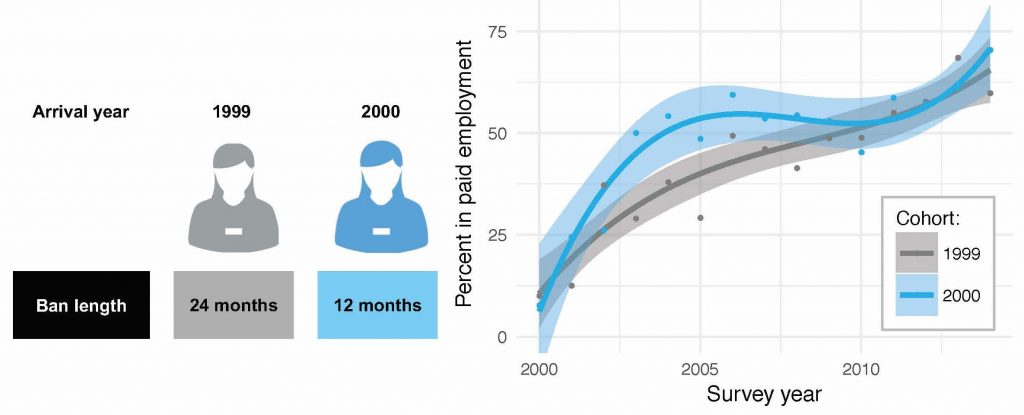

The IPL researchers cut a path through this confusion with the help of a 2000 court ruling in Germany that shortened the country’s employment ban to 12 months. Asylum seekers who arrived in 2000 had to wait 12 months before applying for jobs, while those who arrived in 1999 had to wait between 13 and 24 months.

The timing of the ruling was also a boon to the researchers. When the new policy took effect, the overwhelming majority of new arrivals from parts of Yugoslavia, then at war, were asylum seekers. Using Germany’s annual, representative survey, the Mikrozensus, the researchers zeroed in on Yugoslavians who arrived in either 1999 or 2000: two groups that look identical in nearly every way except for an average 7 months of forced unemployment.

Long-Term Consequences

At first, both groups had low employment rates once they were allowed to seek work, but those who had the shorter wait soon pulled ahead of their peers. Five years in, about half of the 2000 group were employed (49%), while only 29 percent of their 1999 counterparts had had the same success. It wasn’t until 2010, ten years after the new policy went into effect, that the laggards closed the gap.

This divide can’t be explained by broader changes in the economy, the researchers found. Fellow Yugoslavians who arrived in 2000 and 2001 found work at similar rates. So did Turkish immigrants who arrived in 1999 and 2000 and weren’t affected by the employment ban, since most of them weren’t seeking asylum.

So how can just seven months’ difference account for such a wide, persistent gap between the two groups of asylum seekers? And why didn’t the earlier arrivals benefit from additional time in the country to acclimate and build social networks that might provide onramps to employment?

Extended, involuntary unemployment can be powerfully demoralizing, a phenomenon other studies have called “scar effects.” Facing a much longer wait may have drained the 1999 group of motivation, and when the employment ban finally lifted, that motivation didn’t suddenly snap back into place. Despite their lower employment levels, researchers found, this group was less likely to have searched for a job in the days before survey-takers interviewed them.

Refugees might be particularly susceptible to these “scar effects”, the IPL study suggests, because they are new to a foreign country and culture, have recently experienced the trauma of violence or persecution, and lack the resources and social support that help see others through the difficulties of unemployment. “Policies such as employment bans are short-sighted,” says Moritz Marbach, a postdoctoral researcher at ETH Zurich and co-author of the study. “Instead of having refugees depend on government welfare for years, countries can capitalize on their initial motivation and integrate them quickly.”

The findings also illustrate how formative refugees’ early experiences can be. Even modest forms of encouragement and support during this window of opportunity may give them a big lift into integration; barriers, even temporary ones, can likewise have disproportionately negative effects.

Consider the high price of Germany’s employment ban. If the 40,500 Yugoslavian refugees who arrived in 1999 had been allowed to work just seven months earlier, bringing their employment rates up to the level of the 2000 arrivals, the country would have saved about €40 million per year in lower welfare payments and higher tax contributions. Meanwhile, native workers don’t necessarily benefit from policies keeping refugees out of the labor force. Previous studies have found that allowing refugees to work doesn’t lower natives’ wages or make them more likely to be unemployed.

The irony is that the employment ban is motivated in part by policymakers’ desire to reassure the public that refugees won’t compete for their jobs. However, when refugees are unable to support themselves and perceived as a drain on the social welfare system, policymakers may face even greater political punishment from the public. Ultimately, policies that improve refugee integration can also benefit the host country. A necessary first step is to consider refugees not as a burden to be mitigated but as a potential asset to be maximized.

LOCATION

Germany

RESEARCH QUESTION

How do temporary employment bans affect refugees’ long-term integration?

TEAM

Moritz Marbach

Jens Hainmueller

Dominik Hangartner

RESEARCH DESIGN

Natural Experiment

KEY FINDING

Asylum seekers who had to wait 7 months longer before entering the labor market were 20% less likely to be employed five years later.