In the fraught world of today’s immigration debates, ethnic enclaves are a rare point where both sides converge. Immigration restrictionists look at these communities, where immigrants speak their own languages and shop, work, and worship among themselves, and worry that the newcomers won’t adopt their society’s norms and values. Immigration advocates, meanwhile, think enclaves risk funneling their residents into an underclass and blocking access to economic opportunity.

These concerns are especially present in Europe, where more than 2 million people have applied for asylum since 2015, and where several countries disperse refugees across locations in part to discourage the growth of enclaves.

While unease about ethnic enclaves is widespread and deeply rooted, it’s based more on optics than evidence. Now, a new study reveals that these fears may be misguided: Regional ethnic networks can actually make it easier for newcomers to gain a foothold in the local economy.

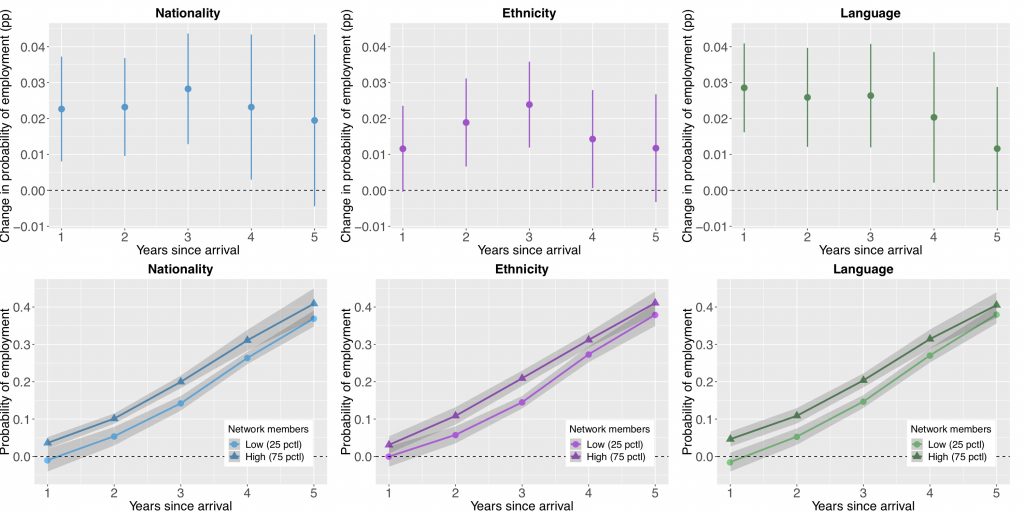

IPL researchers studied recent asylum seekers in Switzerland, and found that they were more likely to be employed if they lived close to a larger group of people who share their background. A 10 percent increase in the size of the ethnic network boosted employment by 2 percent within the first years after arrival.

“Our study shows that ethnic networks can catalyze the economic integration of refugees,” said Linna Martén. “These networks can play an important role in supporting refugees as they navigate the host country’s labor market during the critical first few years after their arrival.”

The findings suggest that ethnic communities are not necessarily the barrier to integration that many believe them to be, and they offer new insights into an underappreciated support system refugees rely on as they rebuild their lives in a new country.

Insights from Switzerland

Switzerland offered the researchers a golden opportunity to uncover the influence of asylum seekers’ social networks. First, since the country allocates asylum seekers virtually randomly across its 26 member states, or cantons, they could compare asylum seekers who were similar in just about every way except for the canton they landed in. (Partly because of this policy, Switzerland does not have “enclaves” in the traditional sense, but cantons do vary widely in their concentrations of various immigrant groups.) If the asylum seekers could choose where to live, those who opted for areas with plenty of their fellow countrymen might look very different from those who preferred to live outside these communities, and it would be impossible to isolate the effect of the networks from the many other things distinguishing the two groups. Second, Switzerland requires refugees with “subsidiary protection” to stay put for at least five years, which means their exposure to these ethnic communities remains stable as the different groups are followed over time.

Switzerland also provided richly detailed data on each refugee. In addition to demographic profiles, the government recorded their employment status at the end of each year, their employer, the date they began working, and the kind of job they held. And the data allowed the researchers to measure refugees’ social networks not just by country of origin but also by ethnicity and language—potentially important distinctions for countries whose diverse populations live within the same borders but have little else in common.

When the researchers homed in on refugees who arrived between 2008 and 2013, and tracked each new cohort for five years, a subtle but persistent trend emerged. Refugees who were assigned to live in cantons that happened to have greater numbers of people like themselves (whether shared nationality, language, or ethnicity) found jobs sooner and held those jobs more consistently. Women, who usually have employment rates of just 8 percent on average, benefitted the most from proximity to members of their own social group.

While early employment tends to be a stepping stone toward longer-term integration, it isn’t a guarantee. Newcomers may be industrious but stuck doing unskilled work within their ethnic community. Yet when the researchers looked more closely at those who were employed, they found no sign that they were clustering in low-wage jobs.

Could it simply be that places with lots of immigrants are friendlier to refugees? Apparently not: When “network” was defined just by the number of immigrants, and not the number specifically with the same background, there was no positive effect on employment.

Networks and Newcomers

The likely explanation, the researchers thought, was that news of job opportunities spreads by word of mouth among members of the same social group. The data, it turned out, suggested this dynamic. Whenever refugees shared the same employer, they were also highly likely to share their ethnicity, country of origin, or language. Of those who were working, 60 percent had an employer who had hired at least one other person from their country in the past, and the share of co-national coworkers was more than twice as high within firms as within work sectors. In other words, refugees from, say, Somalia don’t gravitate toward specific sectors, such as restaurant work or construction, to the same extent as they gather around specific employers.

These findings point to a practical value of ethnic networks, something that may be lost when asylum seekers and refugees are widely dispersed. Imagine you’ve just landed in a new place that bears very little resemblance to your home country. One of the first things you’re likely to do is seek out people from home who can help you navigate and get settled. Those connections can give you tips for your job search, put in a good word with their boss, or provide an introduction to someone who can open doors. While social networks can be helpful for any immigrant, they may be especially important for refugees, who may have experienced trauma at home and face stress and uncertainty as they await a decision on their asylum applications.

At a time when unprecedented numbers of people around the world have been forced from their homes, the countries receiving them are intently focused on refugee integration, often with a focus on their employment. What would they do differently if they appreciated how ethnic networks can help channel refugees into work and self-sufficiency? Allowing refugees to tap into these organic support systems wouldn’t cost much money or require the creation and administering of elaborate new programs, but it could make a difference. Ultimately, policymakers tasked with integrating these vulnerable populations must consider not just how to share the responsibility among different regions but also how to set them up for success.

LOCATION

Switzerland

RESEARCH QUESTION

For newly arrived refugees, how does proximity to ethnic communities affect employment?

TEAM

Linna Martén

Uppsala University

Jens Hainmueller

Dominik Hangartner

RESEARCH DESIGN

Natural Experiment

KEY STAT

Since 2015, more than 2 million people have applied for asylum in Europe.

FUNDERS

European Research Council (ERC)